Steel isn't strong, boy!

The Steel Industry is reaching a crisis point. Producers shrug at a new coal mine. Europe's steel sector is struggling to go green, and the government sticks a plaster on energy prices.

2023 is set to be like 2015

Since my piece on Britain’s steel sector, the situation has deteriorated at an alarming rate. Events are moving faster than I imagined, and the crisis looks comparable to that of 2015-2016. For months there have been negotiations over new subsidies to prevent a downscaling of operations and fund new electric arc furnaces (EAFs). In January, the government offered both Jingye (owner of British Steel) and Tata Steel £300 million each. Tata had originally asked for £1.5 billion in funding when negotiations began in 2022 while Jingye asked for £1 billion.

This offer was not taken well. In February, Jingye proposed to close its coke oven, meaning 260 jobs would be at risk. Coke ovens essentially cook different sources of coal (with varying characteristics like phosphorus and sulfur content) into coke, which is then combined with iron ore and limestone to make steel in a blast furnace. Coke can either be produced at a steel mill or imported. That negotiations are still ongoing suggests Jingye is turning the screw on government negotiators.

A coke oven closure is irreversible. Jingye might be using the move to affirm that, if the government provides the necessary subsidies, it will move to ‘green’ EAFs. They have reportedly asked for £1 billion to do this.

Counting Tata and Jingye’s collective requests at £2.5 billion, this would be more than the gross value added of the entire steel industry. This does not even factor in potential handouts to the third big steelmaker Liberty, which recently planned to axe 440 jobs.

British Steel CEO Xifeng Han said British steelmaking was uncompetitive due to high energy costs and environmental regulations. No sh*t Sherlock! This was evident in 2020 when Jingye bought British Steel for a measly £24 million. Its decision to purchase such a dubious asset is itself suspicious. While it promised £1.2 billion in investment, up to 2022 it invested under £200 million. It may be seeking to circumvent sanctions on Chinese Steel to access the European market, but then why not invest? It might be seeking to access intellectual property on long steel products. But honestly, what does the British industry have to teach Chinese Steel, which produces more than the rest of the world combined?

Regardless of how large the next bailout is, there is very little reason to believe the current owners of Britain’s largest steel assets will wait long before threatening to close down again.

A Shadow over Whitehaven

December 7th, 2022, a day that shall live in infamy. The levelling up secretary Michael Gove approved, for the first time in nigh on thirty years, a British coal mine in Whitehaven, a coastal town in Copeland, west Cumbria. The purpose of this coal mine, funded by Australian private equity group EMR Capital, is to produce coking coal, which will service the UK steel sector, reduce dependence on imports of coking coal, and provide export opportunities by supplying the European steel industry. There is just one issue — the British steel industry has largely spurned it.

Jingye is uninterested in British coking coal now due to the closure of its coke oven. Before, it confirmed it would never use domestically produced coal. Tata has been more tight-lipped but has made no firm commitments. My inclination is that these companies are hoping to have their transition to EAFs paid for heavily or even fully by the government. They likely see the potential increase in the viability of their coal-powered mills being a hindrance to further negotiations.

The primary critic from the steel industry was Chris McDonald, the Chief Executive of the Materials Processing Institute, and probably the most visible authority on British Steel beyond the representatives of the major companies. He notes the high sulfur content of British coking coal, the lack of interest from the producers, and the rise of green steel in Europe.

On most metrics, the coking coal produced at Whitehaven should be adequate for coking mixes in Britain and within Europe. The one exception to this is the high sulfur content. Since coke ovens use mixes of different coals, this can be offset by the use of low-sulfur Australian coal. Other characteristics like low phosphorus content counterbalance the sulfur problem. Desulfulphization processes for high-sulfur coal are present, but it is not clear if this capability is in Britain. Overall, there might be some limited inefficiencies to the coking coal from Whitehaven, but it should be mitigated by the short transit costs to the UK, the EU, and Turkey — compared with American coal.

Ultimately, this is a privately funded venture that will have a minimal impact on emissions, will provide some jobs to a deprived area, and potentially alleviate the trade deficit (in a very small way).

Should it flounder due to a swift European and British transition to ‘green steel’, then that will be that, but I am skeptical such a transition will be so swift as to make the mine redundant.

Is Europe’s Green Steel a Pipe Dream?

There is a proposition that Europe’s transition to green steel is accelerating and therefore makes coking coal exports to Europe a non-starter. I would not be so sure. This excellent graphic from Seb Kennedy, an energy analyst and optimist for green steel, shows Europe’s steel market is increasingly dominated by imports of ‘dirty’ steel from high emitters like India and China.

Kennedy points out that for major European countries, steel imports are increasingly accounting for more emissions than domestic steel production and exports. The implication is that their industries are not being replaced with clean production, but are being plugged by dirtier cheap imports.

Funnily, enough, one country that this does not apply to is Austria, whose steel industry is 90% coal-reliant, but is doing rather well. Not being a climate leader has its advantages.

Kennedy goes on:

In essence, European efforts so far on decarbonizing steel have not merely been for naught, they have been counterproductive. Kennedy stresses that, with new tariff regimes coming through between 2026 and 2034, dirty imports will have their prices matched to Europe’s domestic production. Any tariff revenue can be used to fund ‘Green Steel’.

Green Steel can mean a number of things, but for the most part, it means more electric arc furnaces. These already make up 44% of EU steel production but mean more electricity demand at a time of rising prices, and they cannot make steel of certain qualities. Kennedy pours cold water on replacing coal-powered oxygen blast furnaces with hydrogen. They would massively increase energy consumption per tonne and have not moved beyond the pilot stage. An EU parliament brief, though championing the prospect of hydrogen as a replacement to coking coal, admits the price would likely remain higher permanently. Here is one of its findings:

Here, the consumption of steel is basically treated like obesity. Bluff old traditionalists would say you would have to choose between increasing the price of domestically made steel and increasing barriers to imports if you wanted to avoid industrial stagnation. But what do they know?

The Government’s Sticking Plaster

The British government’s steel strategy is as rudderless as its energy strategy. It has decided to approve West Cumbria Mining, but all of its potential funding for UK steel producers is indexed to their decarbonization. The 2019 Tory manifesto pledged a £250 million clean steel fund. The spirit of that fund exists in the bailouts currently being negotiated. While coal-powered furnaces will almost certainly exist in Europe for decades, their closure in the UK is likely.

More broadly, the government’s solutions to growing energy prices for energy-intensive industries like steel show they do not grasp the scale of the problem. The UK government has acknowledged that its emissions trading scheme is hurting the competitiveness of steel. To counter this, Kemi Badenoch and Grant Schapps have announced the ‘Industry Supercharger’. Despite the vitalistic branding, this is a mundane additional package of relief and exemptions from renewable energy commitments for big industrial operations. It also explores relief over network costs.

The Supercharger scheme reinforces the aim of the Energy Intensive Industries Compensation Scheme. This scheme, rolled out in 2017, was aimed at reducing the negative effects of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), which has now been replaced by the more deleterious UK ETS. A scheme reinforcing a scheme to tackle the fallout of another scheme, which has since morphed into an expanded scheme. Nuclear energy might be declining in the UK, but our policy generation is more fissile than ever.

Government announcement of the Supercharger Scheme, Source: UK Government

These exemptions might be better than nothing, but they are far from sufficient. There is something fundamentally contradictory about taxing carbon to dissuade intense energy consumption and then offering convoluted exemptions to energy-intensive industries.

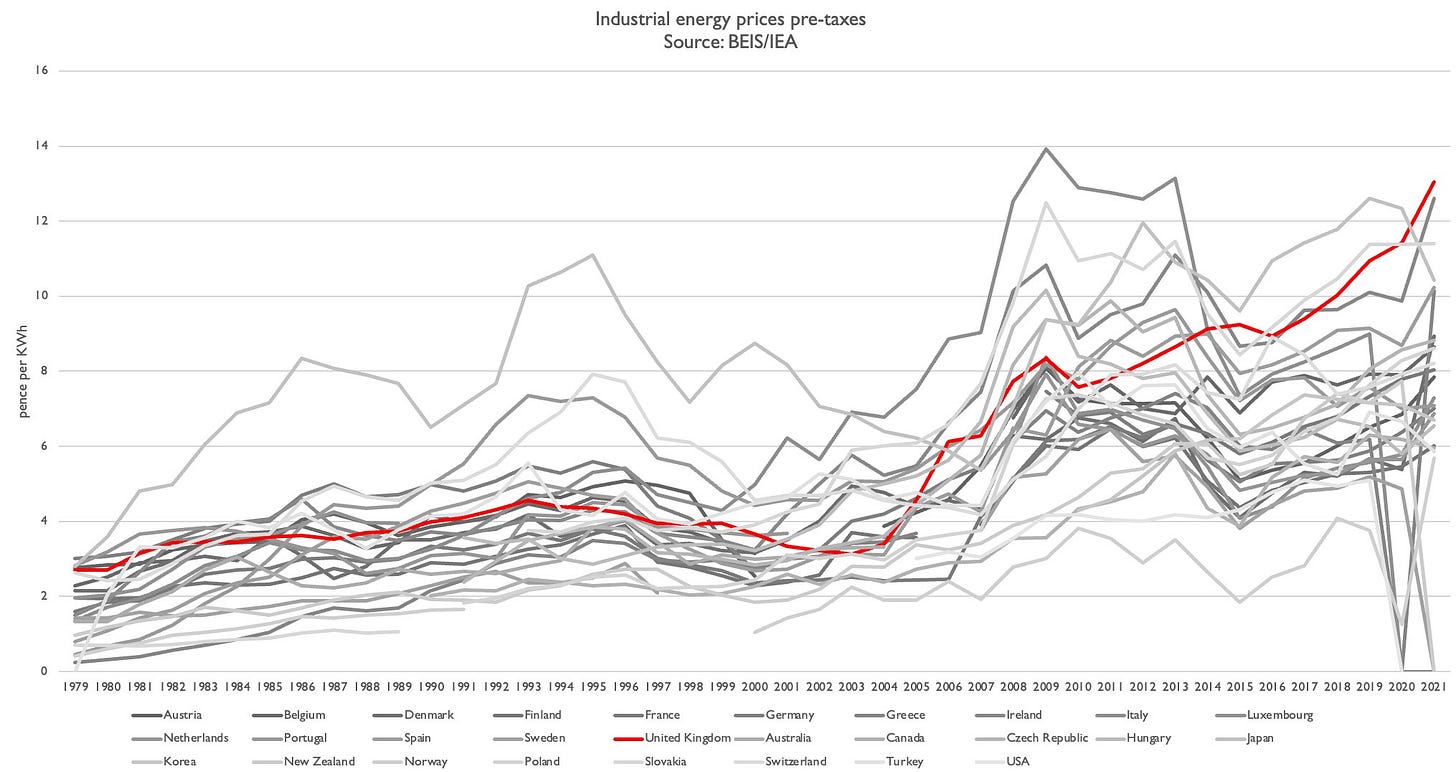

In my previous piece, I documented how both the poor state of the UK electricity grid and carbon tax policies heaped prices on British steelmaking. While the latter is a significant problem vis-a-vis our European competitors, the more existential problem is the pre-tax rise in electricity costs due to our malformed grid. As shown below, Britain’s industrial energy price rise is most notable pre-tax and corresponds to both the rapid expansion of intermittent renewables and the concomitant decline in baseload capacity.

Pre-tax industrial energy prices, Source: UK Government via Ed Conway

You cannot rebate or exempt your way out of this long-term trend. The cost of these exemptions will be paid for by the consumer, and so reduce demand. These exemptions are at best a stopgap.

I will seek to be more positive about steel in the future. That will mean looking abroad.

Thank you for that excellent summary.

When the relevant bills come up for a vote, how many MPs will have read even a summary like this one?