The Riddle of British Steel

I can be flat or long. I can be dirty yet stainless. I cannot be allowed to fail, but am taxed into oblivion by carbon pricing. What am I?

Steel is perceived as a bygone industry, especially now that Chinese supplies have taken over half the global market. In fact, by and large, developed Western and East Asian nations have held onto their steel industries and found ways to be profitable. The EU is the second-largest producer of steel in the world. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan all have strong steel sectors. The U.S. is still the fourth largest manufacturer of steel. There is however an outlier in this story of resilience, Great Britain.

While other countries have mitigated decline, specialized, and in many cases thrived, British steel is performing very poorly. It is worth examining some of the unique factors that make British steel uncompetitive and asking what the prospects are to improve the situation.

At its peak in 1970, the British steel industry employed over 300,000 people and produced 28.3 million tonnes of steel, placing it fifth in the world behind Japan and West Germany. Much of the decline had already happened by 1980 as annual production fell to 15 million tonnes. From that period, it was stable for decades, being over 12 million in 2013. In 2021, production is just 7.2 million tonnes, with 33,000 employed throughout the entire supply chain. The UK is the 24th largest producer globally, behind Italy, Spain, Austria, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Poland to name a few. Even in the context of the United Kingdom’s wider deindustrialization, the performance of the steel industry has been abysmal, declining in real terms by over 50% across the last thirty years even as wider manufacturing output has remained stagnant.

The export-import balance for steel was roughly stable for the noughties but has trended towards greater imports in recent years. The UK has weakening domestic demand for steel due to a longer slowdown in manufacturing and an abrupt decline in the automotive industry post-Brexit, and its high energy costs make it uncompetitive in international markets. This is not a case of expanding imports to meet growth in demand. Rather, it seems a lame industrial sector is limiting the scope for domestic steel consumption, and domestic production is just declining at a faster rate than imports. Weak steel is an effect of a lame manufacturing sector. But it also contributes to it. Not all steel is created equal, and the more Britain needs to source steel products from abroad, the more it is at the mercy of conditions in other countries.

Market Basics

There are two principal modern methods of making steel. You can recycle scrap steel in an electric arc furnace (EAF). Or you can use basic oxygen furnaces. Here iron ore is reduced by coke sourced from burning coal. This produces liquid iron that is saturated with carbon. It is then processed into steel as carbon is removed by supersonic injections of oxygen.

For blast-basic oxygen furnaces, the energy composition is primarily coal, with limited amounts of electricity, natural gas, and other gases. For an EAF, it is 75% electricity and 25% natural gas. EAFs are cheaper, less dirty, and increasingly used, but their emphasis on recycled steel limits the range of products and qualities they can be used for. They also require more electricity. Therefore, oxygen furnaces with coke-fuelled blasting remain competitive. This requires coal as well as electricity. The hope of many is that they can be replaced by furnaces that use hydrogen, as exemplified by Swedish projects. But hydrogen drastically increases the demand for electricity consumption. It is a privileged project for those with functional steel industries and not an ideal option for British operations.

Britain’s Steel Assets

In 2021, 82% of Britain’s steel is based on oxygen facilities at Scunthorpe and Port Talbot, and 18% was from EAFs from Cardiff and Sheffield. Britain is lopsided in having little EAF presence, with most countries having more of a balance. Britain was tailored to the blast furnace in part because we had adequate local reserves of coal and iron ore until recently. We have also had fewer recent investments.

Besides primary steel production, there are individual product categories including long products (like wires, rebars, merchant bars, and rails), flat products (like coil), and other categories like stainless steel. There are also breakdowns by grade: from general construction, pipeline, shipbuilding, and ultra-high-strength grades used in submarines. Steel, while a commodity, can vary hugely, so there is quite a lot of potential for niche players and high-profit margins. Maintaining supplies of the right steel categories for sensitive industries is important not just for global competitiveness but for material security.

British steel assets have been defined by chaotic changes in ownership. British Steel, centered around Scunthorpe, was privatized in 1988 and merged into a new company in 1999. In 2007, this company was subsequently bought by Indian steel producer Tata, which sold its British assets to Greybull Capital in 2016. These assets were sold again in 2020 to Chinese steel producer Jingye Group. Jingye has broken its investment promises and threatened to close down part of the mill unless the department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) provides it with more cash.

Tata still owns the other major steel mill at Port Talbot in Wales and assets further down the supply chain in the West Midlands and the North East. Much like Jingye in Scunthorpe, Tata is in negotiations with the government and is threatening to close the plant if state aid is not forthcoming.

Jingye and Tata are followed by Liberty steel group, owned by Indian-born British businessman Sanjeev Gupta. Gupta himself became famous for acquiring dozens of supply-chain assets over the last decade with the help of Lex Greensill and his financial firm Greensill Capital. He was touted as a potential savior of the industry as recently as 2016. He marketed his steel operations as environmentally friendly, coining the term GREENSTEEL. The subsequent fall of Greensill Capital in 2021 has jeopardized Liberty and their future in UK steel is uncertain.

With Jingye and Tata seeking government support, Liberty’s future in doubt, and the nation at the start of a potentially long recession, the potential of an existential industry-wide crisis over the next 72 months is plausible.

Picture 1: Major steel assets in the UK 2022, Source: UK Steel

There are many other UK steel assets centered around tubes, pipes, processing, rolling, and distribution. Major foreign companies with UK steel assets are Spanish Celsa Group, Italian Marcegaglia, Singaporean Aar Tee, Belgian Bridon-Bekaert, and Kuwait’s National Industries Group. The largest UK-owned operation is Sheffield Forgemasters, an electric arc furnace that was acquired by the Ministry of Defence in 2021.

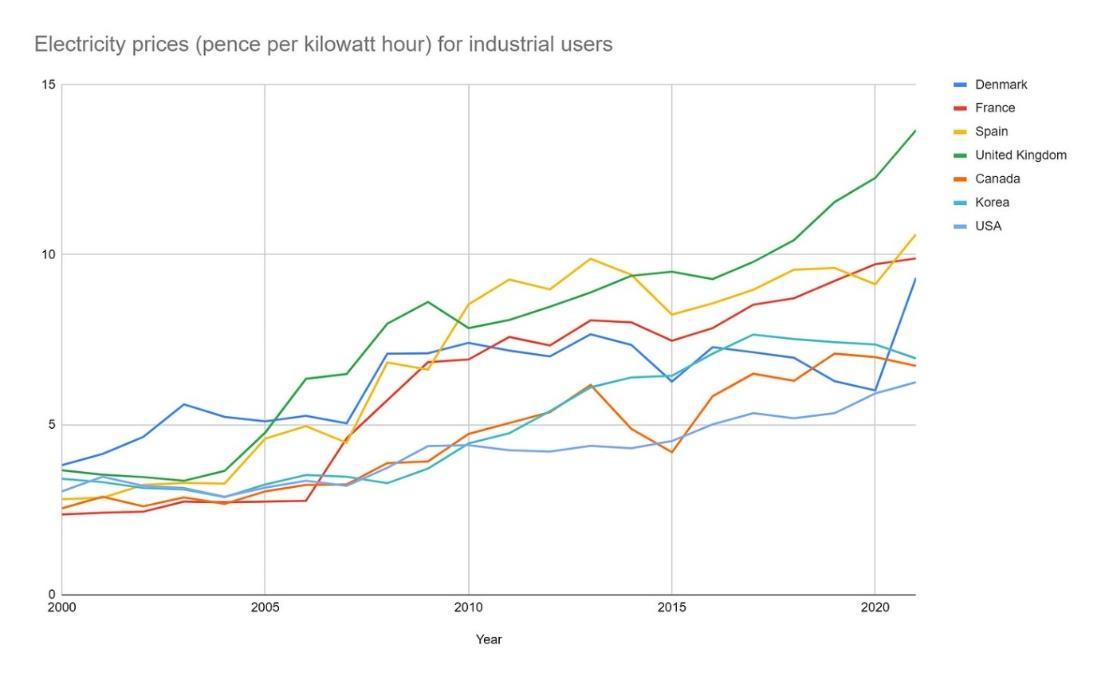

British Energy Price Exceptionalism

The biggest complaint from UK steelmakers to the government is the cost of energy. Coal is priced on the global market and natural gas is a small input. The price of electricity is, therefore, the most determinative. It was in the noughties when the British balance of trade in energy began to deteriorate, resulting from reduced production in the North Sea. At the same time, more renewables and fewer baseline sources (coal and nuclear) increased network and transmission costs. Climate-related policy choices have also made Britain’s electricity prices very uncompetitive for big industrial users like steel.

Looking at industrial energy prices, Britain clearly faces higher costs than most other Western nations.

Picture 2: Industrial energy prices. after taxes. Source: BEIS

But these industrial energy prices from BEIS are quite limited. According to UK Steel, Britain’s steel trade association, they present a misleading picture, as they do not accurately capture all the various exemptions and compensations given to EU competitors and thereby the commercial reality experienced by steelmakers. More discrete analyses from Make UK’s research argues average electricity price UK steel producers faced in 2021 reached £46 per megawatt-hour (MWh) compared to the estimated German price of £25/MWh. This is a surcharge of £21 for every MWh. Therefore, UK production sites are paying over 80% more than German competitors. Alarmingly, the report finds that while wholesale costs can go down year by year, network costs and policy costs are continually rising.

Network costs refer to the prices associated with supplying electricity from the grid to steelmakers. Britain has less secure baseload coal or nuclear power than France or Germany. The complications of having a high proportion of intermittent renewables in our energy mix (without the corresponding investments in new transmission infrastructure) make our costs higher.

Picture 3: Energy prices for steel producers, Source: UK Steel

This problem could get worse. In 2022, the energy regulator, Ofgem, was supposed to implement major reforms from the Targeted Charging Review (TCR), which would increase network charges even further for steel producers. The implementation has been delayed to 2023. If it goes through, UK Steel is arguing it could lead to UK producers paying 156% more than Germany. This will also entail paying more than any major European or anglosphere steel mills.

Then there are policy costs. These include renewables obligations. The German government has minimized renewables levies on its most energy-intensive industries. As a result, renewables costs (after exemption) for steel companies examined in Germany are almost £3/MWh, half the £6/MWh in the UK. The 2013 energy act meant the UK had a higher carbon price than the EU, and that we had a capacity market. A capacity market is designed to fund additional capacity at power plants to ensure energy security and is in part paid for by levies placed on big energy consumers. Looking at the first 5-year review for the capacity market, it seems to be justified on three grounds. Reductions in baseload output in recent decades have hurt British energy security. There is a missing money problem (no one wants to build more baseline capacity because they do not think it will be profitable). Finally, the electricity system is evolving (meaning there is an ever-greater reliance on intermittent renewables). I think the missing money problem can be summarized by the travails of getting the Sizewell C nuclear plant up and running:

Picture 4: Sizewell C status 2012-2022, Source: Wikipedia

Much of these additional costs then are related to bad energy planning. But a large proportion is expenses due to deliberate government policy regarding carbon taxes. We are taxing less carbon-intensive steel for its carbon intensity and so rewarding producers who are more carbon-intensive. The pricing bias against British steel is maddening given our carbon intensity for production is less than the global average at 1.6 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of crude steel. The average is 1.8 tonnes. The European and U.S. averages are lower due to more investment in electric arc furnaces, meaning they suffer less from carbon pricing. But Japan, India, China, and Ukraine are higher in carbon intensity. Interestingly, we have made special exemptions for Ukrainian steel imports to Britain, even though they are among the most carbon-intensive in the world due to still relying on old open-hearth technology. It is therefore likely the policy costs on UK steel, though they may have gotten us closer to Net Zero as a nation, have increased emissions worldwide.

Any attempt to roll back or provide additional exemptions for these policies would face stringent opposition. The 2008 climate change act demanded the government publish a strategy for getting to Net Zero carbon emissions by 2050. Hilariously, the 2021 Net Zero strategy was found by the High Court to have broken the Climate Change act, because it had only quantified 95% of the cuts required. A new strategy is due in 2023. The UK is also the first country to pass a binding ‘Net Zero by 2050’ commitment. Any challenges to this status quo would face huge institutional and legal challenges.

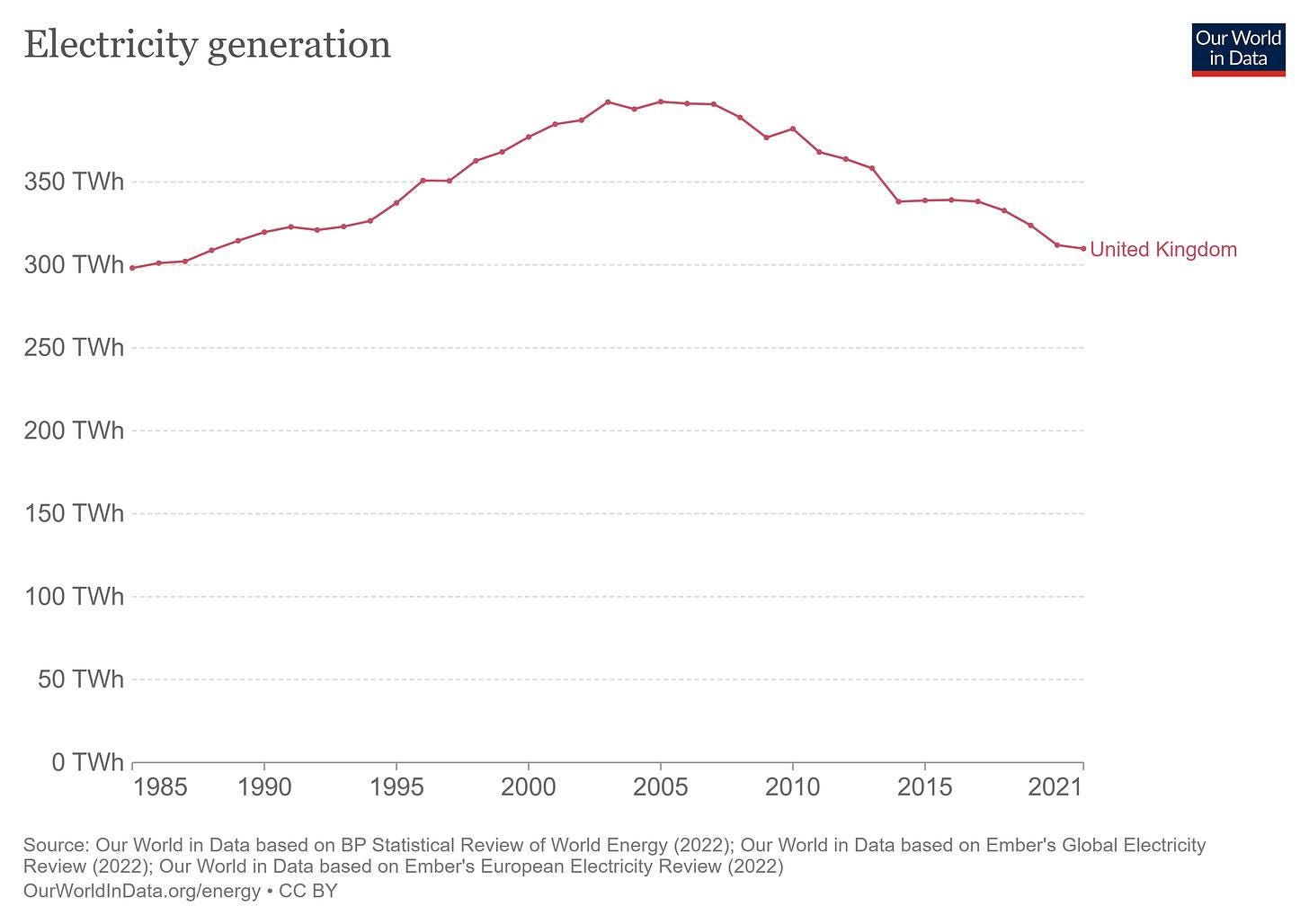

The government wants all future steel investments to be green, but this opens a new quandary. Were the nation to decarbonize steel by switching blast furnaces with hydrogen furnaces and more EAFs, it would consume a lot more electricity. From the UK Steel report:

“Available data suggest that converting the UK’s blast furnace steel production to hydrogen-based steelmaking could increase electricity consumption by 800%, a theoretical shift to 100% electric arc furnace production would increase power consumption by 300%”

But looking at UK electricity generation, our current system is only geared towards gradually generating less. Combining declining supply and exploding demand will just increase prices further.

Picture 5: British electricity generation does not bode well for future needs, Source: Our World in Data

How are you to fully electrify steel while also electrifying transport and heating, even as your wider electricity generation is clearly in decline? There are of course interconnections to European electricity markets, but this assumes Europe has endless electricity to spare.

It is hard to conceive a pathway to reach Net Zero by 2050 without further reducing our steel industry. UK Steel as a body does not oppose Net Zero publicly and tries to showcase its commitment, but effectively acknowledges that barring drastic reductions in the price of electricity, no multinational company would ever invest in decarbonizing British steel.

There are plenty of smaller British steel companies that produce niche products for high-value industries. The lack of competitiveness is not down to some innate failure of British productivity. It stems from energy cost differentials and deliberate government policies. One positive thing that can be retained is the fact this situation is not inevitable but down to policies that could be altered.

The Teutonic Counter

Germany is an interesting counter to Britain. The country’s steel industry has stagnated. From 2010 to 2020, steel production in Germany dropped by around 10% (approx. 4 million tonnes) from 43.8 million tonnes to 39.7 million tonnes. The workforce has declined by about 4,000 to 86,000. This resilience showcases just how many jobs up and down the supply chain can be supported by a large manufacturing base. Relative British weakness in steel is in part due to the weak profile of our industry more broadly.

But it's not just about having a big domestic demand for steel. Austria produces more steel annually than Britain. In 2021 the alpine state of just under 9 million produced 7.9 million tonnes of crude steel to Britain’s 7.2 million. The country has eschewed trying to compete in lower-value bulk products and has instead gone all in on high-end steel. Voestalpine AG, Austria’s biggest steel manufacturer, has built a new, heavily automated mill for robust steel wire next to its blast furnaces in Donawitz to supply automotive manufacturers in Germany. This facility has a capacity of 500,000 tonnes per year with just 14 main operators. That is 35,714 tonnes of steel per employee per year. Though a direct comparison is likely inaccurate, the most productive British plant is Liberty’s Newport, which has a capacity of 5,464 tonnes per worker. This productivity is down to it being a new investment. The latest financial year was the most successful by revenue and earnings in Voestalpine’s 140-year history.

Picture 6: Voestalpine steel mill at Donawitz, Austria, Source: Steel Guru

Austria has succeeded despite having a very similar profile to Britain in which most of its capacity is oxygen-based furnaces (91% in 2021). Voestalpine’s furnaces at Donawitz and Linz are oxygen-based, and not particularly climate-conscious. Austria has seen a good thing and is using tried and tested technology, even if it means lagging in reducing carbon emissions.

Picture 7: Britain’s unique fall in carbon emissions per capita, Source: Our World in Data,

As shown above, Britain really has tested the limits of how quickly a big nation can decarbonize. A great deal of our emissions are exported to the rest of the world through offshoring, so our contribution to global decarbonization is far more modest. But as far as reducing national carbon emissions goes, the government is excelling. Germany and Austria show you can decarbonize slowly and maintain industry. But can you decarbonize rapidly, greatly reduce your reliable electricity generation, and remain competitive in heavy industry? The experience of British steel would suggest no. While a cleaner society is achievable and renewable energy (assuming plus nuclear) could form the basis of a competitive grid with enough investments, these aspirations must be counterbalanced against energy inputs for industry, especially when competing countries are so clearly making allowances for their own.

What Can Be Done?

Within the next 5 to 10 years, the industry outlook could be existential. The government has a number of options; letting the industry go, intervening directly through tariffs and protectionism, and changing carbon pricing to account for dirty imports. The final option is to make special allowances for steel against Net Zero.

Let Go?

Why not just let it die? It is not a big industry after all. There is a legitimate argument that it is far too late to turn these assets around or upskill the workforce. Had we spread R&D more fairly over the last 20 years, we might be in a different position, but that is not the reality.

But as costly as hanging on to the steel industry might be, it is costlier to let it go. Steel is most concentrated in Scunthorpe and Port Talbot (Humber & Wales). The jobs pay good median wages at £38,000. This is well above the regional median in those areas. Given their location in South Wales, Tyneside, and the Red Wall, these jobs are located in some of the most politically competitive constituencies.

If it collapses, those areas likely cannot hold out for the kind of renovation Sheffield’s former steel hub of Kelham Island has received. Kelham retains some of its steel heritage via a museum and has charming pubs with creaky floors. It has also been conquered by the irresistible Shoreditch-style box park — a ‘vibrant retail hub’ for every Deano and Georgia. But Sheffield has two big universities and Kelham is near the city centre. This will not be the case in Scunthorpe or Port Talbot.

Picture 8: The ‘Steel Yard’ in Kelham Island.

The calculation within the government is that letting steel die is actually likely to cost more than perpetual bailouts due to clean-up and welfare costs. Commentators might argue that if we had an automated steel industry like Austria, the jobs would still go. Inevitably some would. The purpose of investing for increased productivity is to get more output out of fewer people. But the productive industry would still be taking place. There would be demands for employment in logistics and white-collar work. You would need control systems engineers in remote parts of the country to service breakdowns and do maintenance checks. A small number of high-value jobs in Scunthorpe or Port Talbot would create outsized demand for local services. Increased profits could be taxed and used to reinvest in the regions. Highly automated manufacturing is definitively preferable to winding down.

Tariffs and Protectionism

Realistically then, abandoning steel production cannot be justified even on grounds of efficiency. The government has therefore decided to keep the industry going by putting 25% tariffs on imported steel beyond a certain quota. The UK has extended its implementation to 2024. The nationalization of Sheffield forge masters in 2021 is also an indication of greater government willingness to take direct control from current stakeholders.

A major argument against tariffs is that they increase the cost of inputs to discrete manufactured goods like cars and airplanes. On the face of it, this is true, but the logic is faulty. Behind every major product, there will be different segments of the supply chain. At the start, you will have material extraction. You then get ‘process’ manufacturing of more general inputs like steel. You then get the discrete manufacture of components and eventually assembly of finished goods like cars. If we want to prioritize the more we go up the supply chain, then the natural thing to do is to reduce the cost of inputs like steel, even to the detriment of local producers.

This assumes that profitability and productivity consistently expand the further down the supply-chain one goes. But this is not the case. Take contract manufacturers like Foxconn. They are primarily responsible for assembly, one of the later stages of the supply chain and one of the least profitable. Or look at the solar panel supply chain. The most profitable parts of that supply chain are inverters (the batteries) and polysilicon (the basic material), while the middle stages of the supply chain, like wafers, ingots, and panels are far less profitable.

If it served us well to forego process manufacturing of steel for discrete manufacturing of cars, you would expect there to be a demarcation in global trade between those excelling in process manufacturing and those excelling in discrete manufactured goods, but there is not. The countries that build the most steel very often build the most cars. Spain is an impressive 17th in steel production for 2021 and is also competitive in car production, reaching 7th globally in 2017. Austria leads in the production of steel and motorcycles. Taiwan, the home of incredibly profitable semiconductor manufacturing companies like TSMC, is also 12th in steel, producing over three times as much as Britain in 2021. There appears to be no discernible scalable advantage in deferring process manufacturing for discrete manufacturing. If there are incremental savings to be made, Britain’s additional costs of energy easily outstrip them. Discrete manufacturing of cars would be better served by reducing electricity costs, not importing steel.

Mercantilists have even gamed international trade by withholding exports on process manufacturing technologies and maximizing exports of discrete goods, with China being a big example. Beijing places value-added taxes (VAT) of up to 13% on refined rare earth metals and the magnets manufactured from them. While finished magnet producers can deduct this tax through exporting, metal suppliers cannot. This allows China to sell high-value components to foreigners while undercutting the ability of others to manufacture their own magnets by limiting access to rare earths. In this case, dominance in process manufacturing creates leverage in discrete manufactured goods. It is a neat trick. We need this kind of capacity for productive chicanery in our civil service.

Tariffs may be required for survival, but are not sufficient to solve the problem. Increased allocation of British steel for public procurement is an option that is already being pursued. Simply increasing public procurement while maintaining protectionism should hold up steel and reap more dividends than just endless bailouts. Courting better stakeholders (more Voestalpines and fewer Greensills) would help. But increased capital spending will draw large institutional battles with the Treasury and will compete with all manner of other spending requests. The government's ability to intervene is therefore limited.

Improved Carbon Pricing

The current UK emissions trading scheme is leading to higher UK costs for electricity and does not account for the suppliers of imported steel, whether in the EU or China. An EU-linked trading scheme could provide stability but would not cover non-EU steel imports. A further carbon tax might make steel consumers think about sourcing from China but would likely lead to lower demand. Fundamentally, steel producers cannot shift the carbon costs of their labour to their customers as utilities can to their consumers.

Protect Steel from Net Zero

As documented, UK steel is fundamentally uncompetitive primarily because of pricing, which is down to the British energy system and government policies relating to the taxing of carbon. There are certainly institutional challenges. The lack of effective domestic ownership amongst the largest suppliers leaves the government with very little control. Nationalization might provide more long-term stability. But it would not curb the cycle of punishing energy costs followed by bailouts. The UK Steel association backs Net Zero even as it acknowledges its effects on its own industry are ruinous. The ill health of the industry prevents private investment which could lead to serious decarbonization. The government has made any future public investment contingent on decarbonization, via the clean steel fund (£250 million) which will be allocated in 2023. But these decarbonized assets would place higher demands on Britain’s already poor electricity generation capacity. Decarbonized industry is contingent on the consistent abundance of electricity, which Britain does not have.

A more aggressive effort should be made to demand reductions in government carbon taxes until they are at par with those of similar European producers. This will be a contentious political battle. Net Zero might be dismissed as a buzzword. But from what I can tell, researchers, civil servants, and ministers care about achieving it far more than growing British industry or refuse to see a tradeoff between the two. Chris Skidmore, the former minister responsible for the 2050 Net Zero commitment, is leaving politics to pursue a career in… Net Zero. Rishi Sunak was effectively bullied into attending COP 27 by journalists. Government-sponsored documents propose meeting the 2050 target by drawing down all commercial shipping and closing all airports. When such radicalism is normalized as legitimate research for policymaking, it is clear that a correction is needed. Britain has already decarbonized more than almost any other major nation. Boris Johnson really did burn the candle in his commitment to COP 26, to what feels like no avail.

Picture 9: Boris catching some sleep at COP 26

We should make the same allowances other major Western economies are making for their domestic steel industry, and counterbalance legitimate climate commitments with being a major industrial society. British steel might not be a large component of the economy, but it is a bellwether for the future viability of British industry at large. We should actively prioritize its success.