Replacing LCREE with the Foundational Industrial Economy (FIE)

Based on the government’s own figures, the ‘Green’ economy is pretty small, and its manufacturing sector is tiny. We need a new arbitrary grouping of industries to refocus industrial thinking.

The Low Carbon and Renewable Energy Economy (LCREE) Survey estimates are the primary government database estimating the size of what’s broadly termed the ‘Green’ Economy. Since a lot of government policy around energy, emissions, trade, and infrastructure has been built on assumptions of a hefty dividend of ‘green jobs’ in the near future, it is worth unpicking. I previously detailed the relatively paltry size of the LCREE here. That was for the 2022 survey, but in July 2025, the estimates for 2023 came out.

Basic definitions

The LCREE is divided into various groups, such as low-carbon electricity and energy-efficient products, among others. These are subdivided into different industries, such as offshore wind or low-emissions vehicles. The turnover from these multiple industries is then split between various sectors of the economy (manufacturing, utilities, construction, etc).

There are two groups where the industry definition is generously stretched. Energy-efficient products include: doors, windows, heating, ventilation, insulation, energy-efficient light bulbs and control systems like smart meters. Then there is the vaguely named “Low emission vehicles and infrastructure”. This means all hybrid and electric vehicles, storage batteries, hydrogen and carbon capture technologies. These are pretty broad descriptions, but not unreasonable.

Big Picture

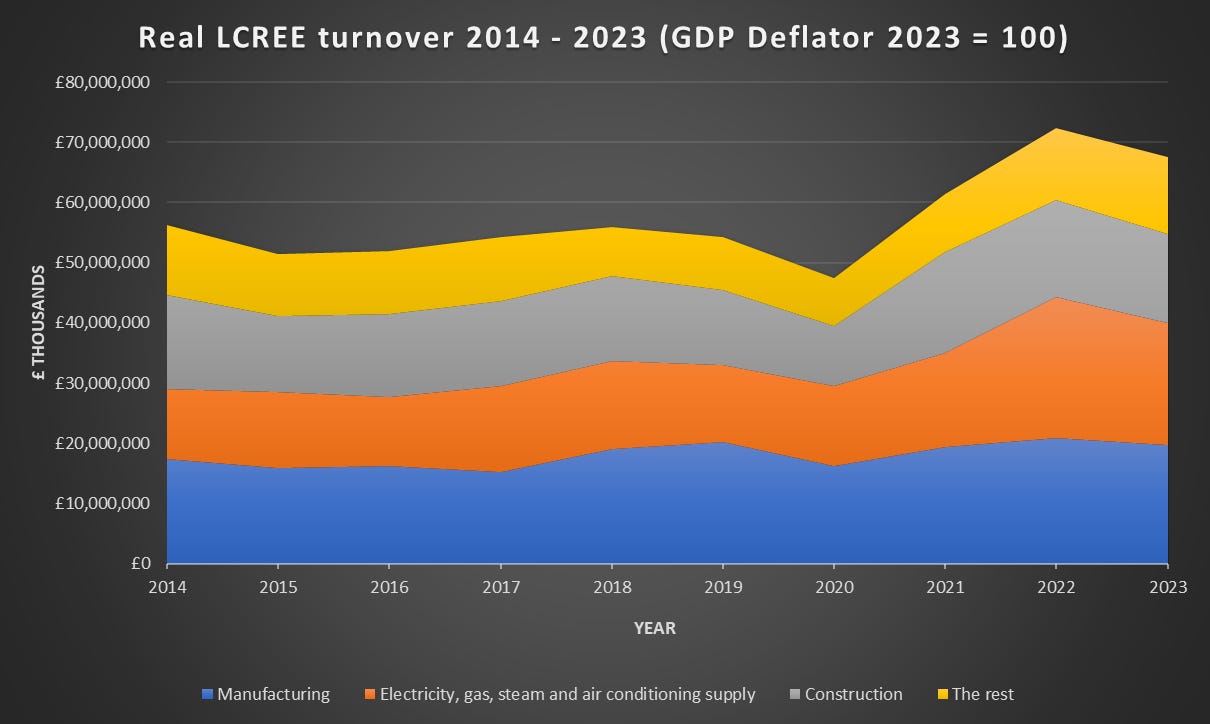

From 2014 to 2023, the LCREE’s total unadjusted turnover grew from £43 billion to £67 billion. This implies a compound average growth rate of around 5% – relatively low when this is considered a high-growth industry of the future, which will take up a large share of British economic activity. When adjusted with a simple GDP deflator (2023 = 100), the CAGR is more modest at 2%. In fact, the estimated turnover of LCREE dropped slightly between 2022 and 2023.

Figure 1: LCREE current and real turnover 2014 - 2023 (calculated with GDP deflator 2023 = 100). Source: ONS.

There are some discrepancies in the data. For example, for 2023, there are currently no estimates for “professional, scientific and technical activities” or “mining.” This might get added in good time and provide a fuller picture, but it won’t significantly affect the overall trend.

It is worth noting that the LCREE overall turnover may sound significant at £70 billion, but it is relatively small beer. For context, British manufacturing has a turnover of roughly £650 billion each year.

LCREE was flat till 2020, and then jumped substantially up to 2022, and has now levelled out again. Why is this? For the most part, it is down to increased turnover in the “Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply” – that is, the turnover of electricity generators.

Figure 2: LCREE real turnover with GDP deflator (2023 = 100). Source: LCREE.

As can be seen below, while the manufacturing share of LCREE has been stagnant, the generation share (revenue collected via electricity bills through government-supported rollout) has grown from 20% to 30% in ten years.

Figure 3: Share of LCREE turnover by sector. Source: LCREE.

While not like-for-like, the rise in LCREE generation turnover tracks that of electricity spending at large. Broadly speaking, as electricity costs have risen, the share of rents going to renewable generators has either increased or remained stagnant. These revenues are likely a combination of wholesale costs, subsidies like ROCs and CfDs, and do not account for increased network charges, other levies going to utilities and the government’s pockets, or capacity market subsidies being given to gas generators. It also does not account for the rents going abroad for imported electricity, which now represent around 12-15% of all consumption.

Figure 4: Final user electricity spending and LCREE electricity spending with GDP deflator (2023 - 100). Source: DUKES Table 1.1.6 Expenditure on energy by final user, £ million / LCREE 2023.

The link between the higher cost of electricity and the higher LCREE is a problem, because while the latter benefits the case for Net Zero and further investment, more electricity spending for less generation is clearly bad. Look at industrial electricity consumption and expenditure on electricity – more costs for quite a bit less juice. This cannot be dressed up as anything other than a decades-long policy failure.

Figure 5: UK 1970-2023 industrial electricity consumption in thousands of oil equivalent (KTOE) and electricity spending (GDP deflator 2023 = 100). Sources: ECUK and DUKES.

Manufacturing

The rise in revenue from electricity generation is not being matched in manufacturing. This should be the preeminent focus of the “Green Jobs” push. In current prices, LCREE manufacturing has grown from £14 billion to nearly £20 billion in ten years, for a CAGR of 4%. Adjusting for inflation, it is basically flat.

The most notable thing is that, when we talk about green manufacturing potential, we are talking primarily about vehicles and building materials. In 2023, for all LCREE manufacturing revenue, 42% was from vehicles and charging infrastructure, and 34% was from energy-efficient products.

Figure 6: LCREE manufacturing turnover by industry 2023 (£19.7 billion in total). Source: LCREE.

Britain has almost no solar and wind manufacturing at all. Out of the £19 billion turnover for the wind and solar industries, just 6% was in manufacturing. The total turnover related to building wind turbines and solar panels is about £1 billion.

Figure 7: Offshore wind, onshore wind and solar industry breakdown 2023. Source: LCREE. Note: No figure for onshore wind manufacturing is given.

When Ed Miliband walks around a wind turbine factory and says that the possibilities for Hull are limitless, others should actually remind him what a little stage he is gesticulating on. The government knows this is a problem. For the latest CfD auction, it has brought in a clean industry bonus scheme to incentivise local investment.

To give a sense of the size of our wind and solar industries, here is the turnover for some selected industries with higher 2023 turnovers from the 2024 ONS Business survey:

Manufacture of beer - £9 billion

Distilling, rectifying and blending of spirits - £8 billion

Manufacture of articles of concrete, cement and plaster - £7 billion

Forging, pressing, stamping and roll-forming of metal; powder metallurgy - £2 billion

Manufacture of abrasive products and non-metallic mineral products not elsewhere classified. - £1.4 billion

Manufacture of bearings, gears, gearing and diving elements - £1.3 billion

Manufacture of cement, lime and plaster - £1.2 billion

Building of pleasure and sporting boats! - £1.1 billion

Manufacture of carpets and rugs! - £997 million

The tiny size and minimal growth of LCREE manufacturing is concerning, since it is being juiced by government interventions in both our electricity grid and consumer choices. The government currently subsidises heat pumps (renewable heat) by bribing people up to £7500 per installation. It is de facto banning gas boiler installations for new homes via the Future Homes Standard, which will come into force sometime in the next two years.

Britain also has a mandate to reach 100% zero electric vehicle sales by 2035, or 80% in 2030. In 2024, the mandate was 22%, with the actual sales figure being under 20%. Let's consider the heat pump and low-emission vehicle markets relative to the industries they are replacing.

Manufacture of central heating radiators and boilers - £1.6 billion versus £862 million for renewable heat

Manufacture of motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers - £82 billion versus £8.2 billion for low emissions vehicles and infrastructure

The established automotive and boiler industries have been stagnant or declining for some time. We have no effective tariffs on very cheap Chinese electric vehicles, and so our ZEV mandate is steering us away from domestically built cars to imports. There is every chance our government's industrial policy is actually pushing down our aggregate manufacturing turnover. Forced substitution is not the same as industrial growth.

The Foundational Industrial Economy (FIE)

If I were Blue Labour, the Conservatives or Reform, I would use the LCREE to point out that the sacrifices we are making today are not going to translate into milk and honey later on. Overall, turnover for LCREE, excluding electricity generation, is barely keeping pace with inflation.

I propose the foundational industrial economy (FIE). This would include all energy-intensive industries listed by DESNZ, and the entire mining and quarrying sector.

As of 2023, the EII sector is £170 billion in turnover and £36 billion in GVA. The mining and quarrying sector, minus those subsectors already in the EIIs, is £34 billion in turnover and £22 billion in GVA. Combined, they are £202 billion in turnover and nearly £60 billion in GVA. This is 10 X the turnover of the green manufacturing sector (> £20 billion). While the LCREE does not outline GVA, we can expect FIE GVA to be between 7-9 X that of LCREE manufacturing.

Figure 8: The FIE by GVA and turnover in 2023. Source: ONS 2024 annual business survey.

It's important to note that the EII does not cover all revenue in listed sectors. Pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals are not included in the scheme. There are fabricated metal products that are not included. The only subsector of the beverage industry counted as energy-intensive is the manufacture of malt.

The FIE could be expanded to sectors that are not energy-intensive, but very important nonetheless. The EII criteria are not the only potential criteria. From 2023 to 2024, the energy bill support scheme was offered to both energy-intensive and trade-intensive sectors. The FIE could be stretched out further. It is not even antagonistic to Net Zero per se. For example, battery manufacturing is included in the EII criteria.

If arbitrary economic constructs can be used to push Net Zero, alternative constructs can be made to prioritise critical industries. While we would not say the FIE is going to carry British economic prosperity through this century, its health and vitality will be crucial to any prospective attempts at reindustrialisation. There are not too many countries where people cannot make steel, but can scale up advanced robotics and semiconductors. If we are betting on a more turbulent and unpredictable world, then we need the capacity to build the basics.

After over ten years of reporting, it's clear the LCREE is not going to deliver a significant windfall in growth. Its limited size should form part of the debate around shifting away from Net Zero, or atleast separating industrial policy from environmentalism. But policymakers should not just replace Net Zero or the LCREE with odes to gas-powered lawnmowers and complaints about electric vehicles. The FIE must be reprioritised.