Num Deus Volt?

If you can't do steel, your chances of doing batteries are minimal

After a short hiatus in Australia and the U.S. east coast, I am back in England. The primary industry-related stories of the holiday season have been the longstanding travails of the British steel industry and the sudden collapse of Britishvolt, the aspiring developer of batteries. While the British government is willing to cut its losses on Britishvolt, it is continuing to habitually bail out the steel industry. The first bailouts could be £600 million for the deceptively named ‘British Steel' (owned by Chinese Jingye Group) and Tata Steel. Liberty Steel Group, the third largest UK steel producer, may also negotiate subsidies after announcing plans to restructure hundreds of jobs.

While the government was offering £100 million in funding to Britishvolt, this was predicated on construction starting immediately. Now, out of five potential buyers, an Australian lithium-ion battery developer called Recharge Industries has won out. With great irony, one of the potential late bidders was Greybull Capital, a private equity group known for its short management of British Steel. Recharge may make a success of this yet, but they have yet to build their own factory in Geelong, so are not coming with an established pedigree.

Steel before Batteries

A recent article from City AM argues that saving steel while letting the aspiring British battery industry die in its crib is a mistake. The piece makes a valid point about the futility of our government’s continual bailing out of an industry that constantly fails while offering no respite to a potential British challenger in an industry with high growth potential.

But the travails of the steel industry and its non-existent electric vehicle supply chain are connected. After all, China, the world’s largest producer of steel, is also the largest manufacturer of batteries, with 77% of lithium-ion cell manufacturing capacity in 2022. The EU has 14% and the U.S. has 6%. The UK share is 0.2%. As well as being the largest maker of battery cells, China is the leading producer of magnets used in electric vehicles and wind turbines. China is primed to dominate battery cells for a variety of reasons. It mines a large share of the lithium produced globally and is dominant in the processing and refining of key materials. China is the single largest refiner for lithium, nickel, and cobalt — key inputs for cathodes. It is also the leading refiner of graphite, which is critical for anodes. They have a long list of large domestic automotive giants with the capacity to build electric vehicles and the largest potential customer base on the planet. This is supported by China’s incredibly cheap electricity market, with Chinese businesses paying three times less on electricity costs than their British counterparts. This discount adds to the much larger discount in Chinese labor costs.

The level of dominance cannot be corrected through the market, and so European countries have pledged significant assistance to fund at least 35 battery-making facilities up to 2030. This would increase EU manufacturing capacity to around 900 gigawatts per hour (GWh), currently where China is now. But by then, Chinese capacity will expand to thousands of GWh, with it being projected to retain 66% of the market. European subsidies are aimed at reducing dependence on East Asia but face another threat from the provisions of the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

With the U.S. and EU looking to restore a greater share of their supply chain, and China dominating all other markets, Britain is sandwiched between three larger players in a subsidy war. Some would argue that were we back in the EU we would be in a better position. Certainly, Brexit has coincided with a broader reduction in British-made cars and light commercial vehicles. As the UK car industry is primarily built around exports to Europe, greater trade friction would be a problem, but much of the drop can be attributed to the coronavirus and the significant increases in energy costs over the past 12 months.

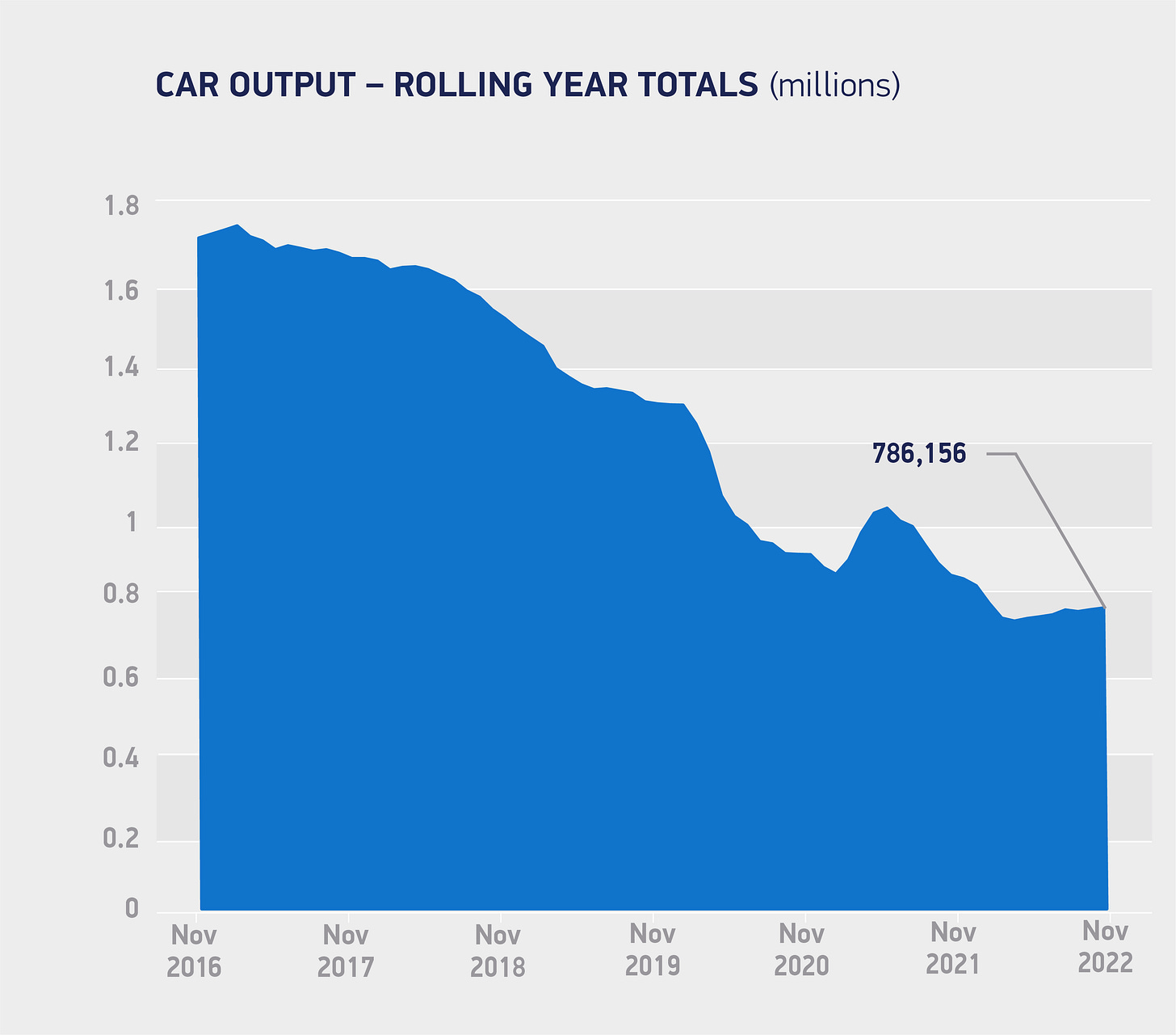

Figure 1: As the British government aspired to be a champion of electric vehicles, car output halved.

Compared to Britain, Poland has an impressive buildout of battery manufacturing sites, having 6% of global capacity in 2022. While Britain’s steel output has effectively halved since the great financial crisis, Polish output has been stable. When comparing 2021 electricity costs for businesses in pence per kWh, very large Polish consumers pay 0.75 pence while British businesses pay 1.38 pence. After-tax, UK energy costs are 62% more than the EU 14. Since 2009, very large commercial UK energy consumers have never paid less than their median EU 14 counterparts. Regardless of Brexit, our manufacturing environment has been unappealing to would-be investors for decades. High energy costs can be mitigated if your country is already a manufacturing powerhouse and you have a large number of large industrial companies whose leaders are integrated within your country’s political economy, like Germany. But for Britain, the lack of established domestic industrial companies, particularly in automotive and steel, high-energy costs can be prohibitive to a successful industrial policy.

Politicians do not have some arbitrary choice about whether to hold up legacy industries like steel or invest in the ‘green industrial revolution’ by specializing in batteries. Both these sectors are energy-intensive and reliant on large domestic demand. The chances you can be a leader in batteries while simultaneously not being a viable destination for steel production is close to zero.

UK government funding might have continued to keep Britishvolt’s project online for years, but with the country in a current account deficit and the Treasury increasingly tying its spending to the whims of testy bond markets, large-scale industrial spending that can convince companies to ignore the enormous subsidies of Beijing, Brussels or Washington is becoming hard to earmark.

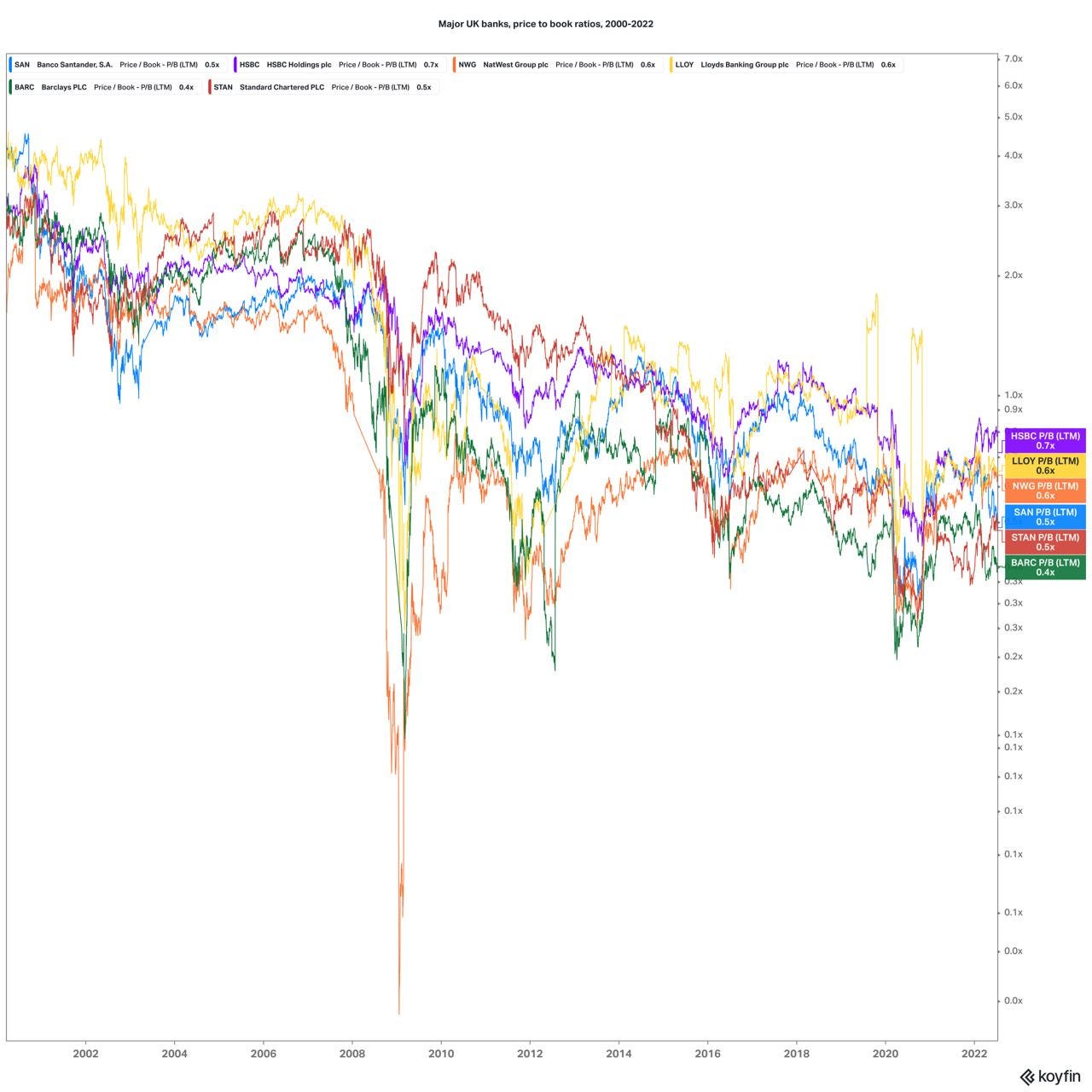

A further problem is the stagnation of UK bank lending versus more healthy economies like the U.S. The chart below shows the ratio of market prices to book prices for major UK banks. In essence, over twenty years, markets have become convinced the stated book value of money lent by British banks is worth far less than what the balance sheets say, in some cases less than half.

Figure 2: British bank price-to-book ratios between 2000 and 2022. Provided by ‘In the sight of the unwise’.

This picture is far less pretty than for equivalent samples in the U.S., Poland, Turkey, and Israel. It most closely resembles the unenviable position of the Italian banks. Like Italy, British economic policy is ever more constrained by the bond markets. The diversion between book value and market value means banks keep bad loans for fear of acknowledging their true worth but are also deterred from investing in innovation or more risky ventures. No discussion about reindustrialization can be isolated from this broader stagnation at the macroeconomic level.

Wider Choices

We have a situation where the likelihood of successful industrial policy is constrained by macroeconomic factors any government is increasingly unable to control. This includes continual trade and current account deficits, cuts to government borrowing, increased fear of bond market reprisals on sterling, and a zombified bank ecosystem.

But there are things the government can do.

The first step is for policymakers and civil servants to improve their understanding of technology and align rhetoric with clear figures so that they might pick more viable champions. The 'GIR’, as previously discussed, is a poor outline for an industrial strategy. The Johnson government was notable for jargon over substance, and Britishvolt exemplifies this. Autopsies of the company’s downfall point out profligate spending, too many yoga sessions, and the Swedish founders themselves as underlying problems. The fact neither of them had experience in automotive or batteries would not fill many observers with confidence. Hilariously, Ernst & Young, the firm responsible for flogging Britishvolt’s remaining assets off, was also deeply involved in developing the company’s strategy — or lack thereof. This extended to Britishvolt sourcing its chief financial officer from the firm. The whole endeavor feels like a crude parody of consulting culture.

The second, more substantive solution is to reduce energy costs by limiting carbon taxes and various climate-related levies. The British effort to reduce carbon emissions has been more successful than any other major economy. A big reason for that is us offshoring our carbon emissions via manufacturing to a much greater extent than the Germans, the French, or the Japanese.

Much of these levies are enshrined in legislation that stipulates production-based net-zero targets. A veteran of the Treasury suggested to me that you could have two but not three of the following things:

A production-based net-zero target

Lead on net-zero at the level of narrative

Have a strong and fast-growing industrial economy

We are currently electing the first two options. This long-lasting conservative government has indeed done more than any large country to decarbonize. The trade-off was weak growth, stagnant industry, and a less self-sufficient energy grid. The UK is also acknowledged to have a sufficient strategy for further reducing emissions than any other member of the G7. This is not translating into better economic performance, a windfall of ‘green’ jobs, new export opportunities, or even that catnip for policymakers – international kudos. Does the undeniable record of decarbonization give the UK more international goodwill than countries like Australia and Canada, which have worse records on carbon? When the Australian foreign secretary feels inclined to use a diplomatic visit to suggest we interrogate our history, you might start to question how much of that coveted soft power we have actually been accruing through hosting COP 26.

I would promote strong industry by slashing taxes on energy prices for businesses and allocating government funding to technologies that have a high chance of massive returns that can be loosely tied to ‘Green’, meaning more robotics and less hydrogen, more satellite launches, and less electric aircraft. Any commitments and progress on decarbonization should be tracked to the G7 average and not place decade-long regulatory vetoes on executive agencies.

The challenge is significant. Labour MPs effectively took the government to task over Britishvolt, and the lack of due diligence does appear to be a problem. But their solution was to just increase the money in the automotive transformation fund. As stipulated, the financial environment is becoming more constrained, not less. The additional largesse Starmer can afford when and if he gets into Number 10 may not be enough to make a difference.

Perhaps the right answer to the green subsidy war is to tap out now and spend where others are not looking. If the U.S., EU, and China are set on dominating these relatively low-margin industries, maybe Britain should pick more speculative technology fields that are underfunded but have potentially higher returns. Why compete all the dividends of electric vehicles away when we could become the home of xenotransplantation? The potential value of replacing broken human organs with healthy animal organs could be in the trillions, and yet global funding for this activity from 2000 to 2019 was around $500 million. While lots of venture capital goes into autonomous cars, the global robotics industry is still relatively small. As the world falls back in love with large-scale industrial subsidies, Britain could be better off avoiding the crowd.