The ‘Green Industrial Revolution’ cannot reverse Britain’s decline. The next leader needs a new framework for industrial revival.

Government documents are important. They are the anchor for future policies. They set the terms of debate within both the civil service and the governing party. They affect attitudes and thinking within private industry. When they are misguided, this can have an outsized detrimental effect on the country’s direction.

The late Johnson government’s 10-point plan for the Green Industrial Revolution (GIR), published in November 2020, is the central framework for revitalizing British industry. Not so much a policy document as a wishlist, it was a key component of Boris Johnson’s leveling-up agenda. The premise is simple. Britain can get in on the ground floor of a large industrial renaissance based on renewable energy and associated ‘green’ advances in transportation and infrastructure. This will have a net-positive impact on the environment and make Britain a climate leader the rest of the world can look up to.

The framework is not without merit. The industrial revolution was a massive force multiplier for Britain, propelled us far beyond other European powers, and massively improved our standard of living. It also served to distribute wealth beyond London. Having another industrial revolution would certainly be beneficial.

The GIR is also popular because it essentially disentangles tensions between environmentalism and industrial progress. Many right-wingers prioritize extraction over nature and are often churlish about the environment. Greens on the other hand argue that the problem is human civilization and the need for growth in the first place. Both these views deal with the climate problem by dismissing the importance of something (nature or human civilization). GIR however is positive-sum. It implies there is no tension between industrial growth and reducing energy consumption. There is a kernel of truth in this. Governments can promote environmental policies while also prioritizing industrial growth. Intensive industrialization has already reduced the percentage of land required for agriculture.

The problem with the GIR is that the associated technologies and their impact will not constitute a sufficient revolution. Not even close. It is at best a set of auxiliary technologies that could feed into a wider industrial policy. But its effects are not going to be sufficient to shift Britain from a declining power to an industrial powerhouse. One of the most cited studies on the potential dividends of GIR is this paper from the University of Oxford. Its highest estimate for savings for the global economy between 2019 and 2070 is £19 trillion. Now for some fag-packet estimates. The U.K. is 2.34% of the global economy today. Be generous and assume that this will remain constant up to 2070. 2.34% of £19 trillion is £445 billion. Spread between 2019 to 2070, that is £8.7 billion per year in dividends. The U.K. in reality will decline markedly in global GDP share, so a more realistic assumption of 1.5% share over 51 years is £285 billion or £5.9 billion per year. Consider then some more specific assessments for expected gross value added (GVA) from renewable energy industries over the next few decades. Based on a 70-gigawatt capacity scenario by 2050, floating offshore wind will provide a cumulative GVA of £33.6 billion between 2025 and 2050, or £1.3 billion a year on average. Total offshore wind GVA could reach £2.6 billion annually by 2050 according to one study. Another analysis argues tidal, wave, and floating offshore wind assets can cumulatively produce a total GVA of £79.6 billion between 2030 and 2050, or £4 billion annually. These figures all represent the most optimistic scenarios in their respective studies.

Then consider the dividends that the U.K. has historically received from North Sea hydrocarbons. Oil & gas production contributed £492 billion in GVA between 1990 and 2021, with an average annual GVA of £15 billion over that period. The U.K. government directly received £374 billion in taxes from the North Sea between 1970 and 2014 – or £8.5 billion on average every year. In 2022, Britain is expected to beat its North Sea record with £17 billion in revenue. So ‘green energy’ could optimistically provide between £4-8 billion annually in GVA. This is between a third and half of what North Sea hydrocarbons could be expected to provide every year. It is worth noting the U.K. has taxed the North Sea poorly, with Norway showing its possible to squeeze up to £400 billion more in government revenue with similar levels of production. So the GIR, at least from an energy standpoint, will be less of a stimulant to the economy than domestically produced oil and gas. Consider other industries it would be worth subsidizing to get better returns. Chemicals, which get very little interest, contribute near £12 billion to GVA. For aerospace, it is £9 billion. In 2050 or 2070, they should be providing far more. This is not a reason to avoid energy transition per se. There are potential environmental, commercial, and security benefits. But green energy will not provide the windfall needed to reverse Britain’s relative industrial decline.

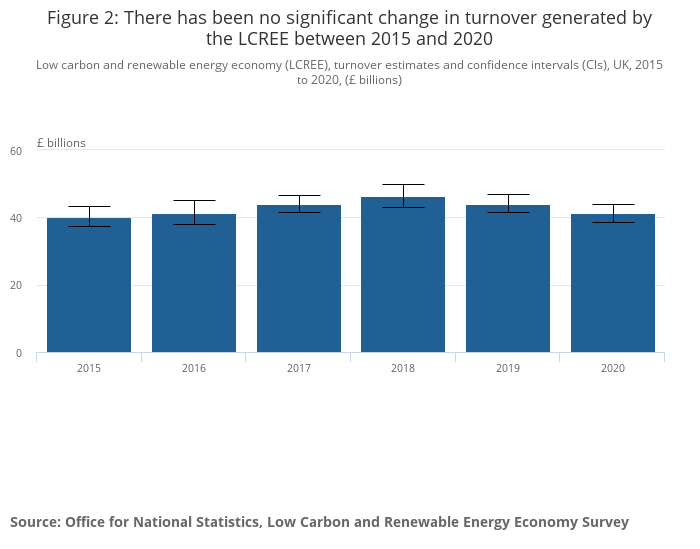

The government document is not just looking at energy but the wider low carbon and renewable energy economy (LCREE), as defined by the office of national statistics (ONS). This taxonomy includes energy and other associated industries to the point it contains large sections of the British manufacturing and construction turnover. This does more to blur the green economy with the traditional, rather than to describe actual growth. 46% of LCREE’s value in 2020 is energy-efficient products and low-emission vehicles (LEVs). LCREE was worth £41 billion in 2020. Though higher in 2019 and projected to rebound in 2021, LCREE has been remarkably static since its taxonomy was developed in 2014. The table below shows this.

Picture 1: LCREE turnover between 2015 and 2020. Source: ONS

Taking the favored estimates, from 2014 to 2019, LCREE turnover grew by 0.3%. If we take the highest confidence intervals for different industries, however, it fell by 2% from £51.6 billion to £50.6 billion. The table below shows that almost all the growth was in LEVs. There were big losses elsewhere, including in solar photovoltaics, advisory services, and onshore wind. Alarmingly, carbon capture and storage turnover decreased by 45% over 5 years. This is partially down to the confidence interval narrowing and being made more accurate as time goes on. But the lack of progress contradicts the Conservative government’s promises about a renewable-led high-growth future. A very large proportion of LCREE is ‘other energy-efficient products’. This broad category includes LED lights, water-saving shower heads, boiler jackets, secondary glazing, and eco-kettles. This also has been stagnant since 2014.

Picture 2: LCREE 2014-2019 breakdown by industry. Source: ONS

Part of the reason for this disappointing 6-year stagnation is that the U.K. is, fundamentally, an importer of ‘green’ technologies. Despite targets for 60% domestic components for offshore wind projects by 2030, under 30% of recent projects use British-made turbines. These are sourced from the Danish turbine maker Vestas, which has a factory on the Isle of Wight, and Germany’s Siemens Gamesa, whose factory is in Hull. In 2017, 93% of British offshore wind assets were owned by foreign entities, with Danish state-owned company Orsted owning 32% of assets. For solar photovoltaics, Britain is reliant on a Chinese supply chain. As for nuclear power, all current plants are owned by the French state. During the initial industrial revolution, Britain was the world’s workshop. Today, it is a consumer of European and Chinese modernity.

The growth in LEVs looks promising at least. Does this speak to a broader strength in the U.Ks motor industry? Probably not. LEV turnover doubled from £3.4 billion in 2016 to £6 billion in 2019. Over the same period, the overall automotive sector’s output has decreased markedly. Below is the monthly unit output for British-made cars. The story is marginally better for light commercial vehicles but the trend is still toward a decelerating automotive sector. Total car production was 1.7 million in 2016 before falling to 860,000 in 2021. Because most British cars are bound for the export market, trade fluctuations and foreign competition can put a huge dampener on production. A more domestically oriented car market with fewer imports would mean more stability but would also require a change in consumer behavior and industrial capacity beyond our current means. Either the growth in LEVs has not mitigated a broader decline, or a greater proportion of produced vehicles are LEVs.

Picture 3: U.K. monthly car production has declined from a high point in 2016. Source: SSMT

LCREE demonstrates neither the size, nor the positive externalities to hold up British industry, and certainly does not amount to the promises alluded to by GIR documents. I think this is tacitly acknowledged by some policymakers and can be seen in the lack of serious money committed to the project. For the GIR, it is £12 billion in government investment and £42 billion in projected private investment by 2030. Within a year, £5.8 billion in foreign investment had been secured for British green projects. So about £50 billion in industrial policy over 10 years, or £5 billion a year (much less if just counting government spending). Keep in mind this is supposedly a whole new industrial revolution – comparable to the birthing of locomotion, coal, steel, and electrification.

Some comparisons are worthwhile. China, which dominates all aspects of the solar industry, subsidized its domestic champions to the tune of $47 billion (£39 billion) between 2010 and 2011. This helped push the Chinese market share of solar panels from 48% to 59% and it has never looked back. Now we are not China. We lack the funds and size. But consider our commitments to overseas development aid, which was £11.4 billion in 2021 after a 20% drop from the 2020 figure. Surely in no serious world is government support for an epochal industrial transformation less than half its spending on foreign aid? If this is so transformative, surely it might also take priority even over defense spending increases? The Ministry of Defence wastes considerable amounts of money and is constantly rewarded for it. A few hairshirt budgets for BAE Systems with more funds shifted to the civil industry could be an unqualified good for the country. It could even improve security by forcing sensible procurement decisions away from flagship projects and towards more affordable systems.

The GIR fails at a conceptual level. Shifting from fossil fuels to renewables will not provide the windfall that mechanization did. The resources set aside to pursue industrial revival are also insufficient. If Britain continues to center its industrial policy on GIR while other countries focus on advanced manufacturing, industrial internet, and expanding energy production, the trajectory towards obscurity will not be abated. Yet both the Conservatives and the opposition stake enormous value in the GIR. If governments throughout this century place their hopes of industrial revival on whatever is ‘green’, the results will be disappointing and fail to pay for the country’s ever-expanding budgets.

Vague Prescriptions

So what should industrial policy entail? Being lazy I have yet to formulate a comprehensive counter-paper, but would be open to such an endeavor. Some initial suggestions for a better framework include:

Energy superabundance - This might seem compatible with the GIR but it is quite different. The emphasis on decarbonization stems from the shift in energy policy in the seventies away from abundance to efficiency. This rather good paper argues that dramatically increasing energy production and consumption can serve as a basis for a wider industrial renaissance.

Geoengineering - While intermittent renewables are a poor platform for industrial society, there are promising technologies that could help accommodate a growing human population without destabilizing the biosphere. Geoengineering is a highly speculative field, but something all far-thinking governments should have on their radar. An excellent introduction to the subject is provided here.

Accelerated automation to increase productivity - As discussed in a previous piece, the U.K. is behind the world average in automation. Regulatory changes, government assistance, more clusters, more factories, weaker antitrust laws…whatever. Set some clear targets on expected robot density and do not just rely on tax breaks.

Exploring import substitution - The most contentious idea and will only likely only be considered in a time of crisis. Will get laughed out of town initially. Import substitution failed in the seventies and eighties, in part due to Britain’s involvement in the EEC and consumer habits. There are a few examples of it working in less developed countries. But setting some targets to reduce the import percentage of GDP from 28-30% to nearer 20% could have huge benefits for the industrial base. This can be applied to both high-tech and midrange durable goods. It will require both tariffs and government subsidies, but should theoretically be very achievable. The U.K.s trade deficit in goods is a relic of the early 21st century, contributing to economic stagnation and regional disparities. There is no reason to accept it in perpetuity.

Importantly, Britain’s trade deficit is an EU phenomenon. This can be mitigated by developing our industrial policy and, if need be, doing less trade with Europe. If Britain is going to do more business with non-EU members, it is worth cautioning against excessive trade liberalization. This piece from American Affairs outlines the rationale of import substitution very well.

Setting up an internal market intelligence firm in government to pinpoint nascent, high-risk industries worthy of subsidies - As a former market analyst in robotics, I only got to speak to government departments via third-party economic consultants they hired to write their papers. Many market analysts would eagerly jump from firms like Gartner and IDC to do industrial strategy. You could pay most analysts under £40,000 initially. It would immediately improve the government’s understanding of technology markets. Issues like 5G cellular connectivity and the security implications of Huawei would benefit greatly from having actual market experts embedded in the government.

Executive action on planning - The shelving of the Oxford-Cambridge arc in the face of NIMBY complaints is but another example of how obstruction to new development is hurting the country. Everyone agrees that more houses have to be built, but everyone is also desperate to keep the situation positive-sum. Unfortunately, some demographics (the young) will have to be prioritized over others (old asset owners). This applies equally to industrial development. Someone is going to be upset. Just push on.

Few power centers would buy into this developmental platform at the present time. But a new premiership, however ill-timed, is a good opportunity to reset policy frameworks and introduce new thinking.