An Appraisal of Rob Rory

A deep dive into Rory's Stewart's memoir. His critiques of politics and government are convincing, but his remedies are found wanting.

Rory Stewart is an undoubted phenomenon. As co-host of the country’s most famous political podcast, ‘The Rest Is Politics,’ he has a flair for celebrity and understands the opportunities of a post-political career. His popularity among my ‘normal’ friends demands that I take him at least moderately seriously. To that end, I have read his latest memoir – “Politics on the Edge.”

Stewart’s oeuvre is not something I sought out. Rather, it was impressed upon me by my primary social circle (not the blackguards who are interested in industrial strategy and heavy forge presses). This milieu is middle-class, upwardly mobile, pessimistic about Britain but optimistic about their place within it (with a few having fled to Australia), generally pro-remain, and able to manage respectable bourgeois sensibilities like accumulating capital, team sports and hard work with heavy drinking and recreational drug use. They are unconvinced by Corbyn, bored stiff by Starmer, repulsed by Farage, and generally exhausted by the Tory party. But Rory, they like.

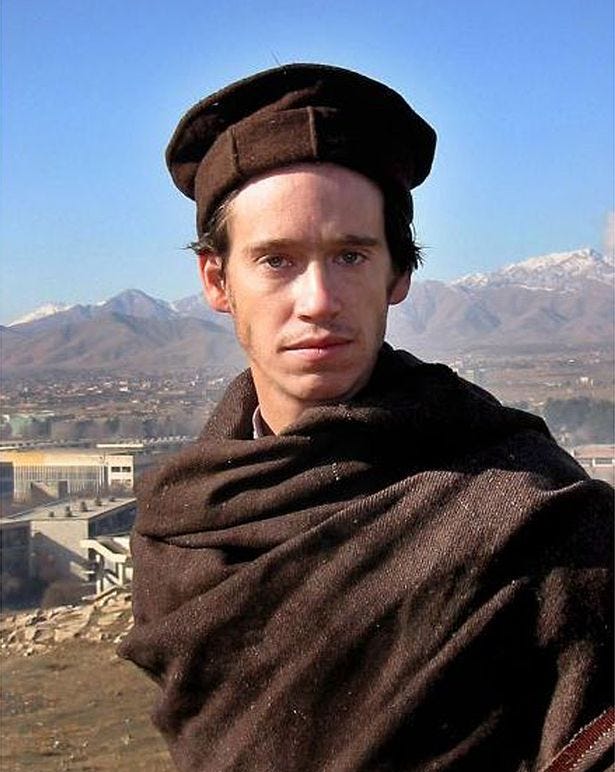

Politics always involves caricatures, and Stewart has built one for himself: Lawrence of Belgravia. He is the forgivable Tory, the idiosyncratic uncle of the nation, the man who uses long words and has great stories about meeting obscure tribal leaders and shady spies.

For a time, Stewart’s life was considered worthy of a feature film, with Brad Pitt being interested in doing a movie. This opportunity dissipated in 2010 with Stewart’s nosedive into retail politics. I do not doubt he will get his moment on screen, most likely played by Adam Godley under the directorship of either Stephen Frears or Michael Winterbottom. It will be an exercise in twee kitsch, and it will be insufferable.

Stewart is stupendously uncommon, although he preposterously asserts he is middle-class. His first memories of food are “bacon and egg sandwiches wrapped in silver foil on a bamboo raft in a Malaysian jungle with my father.” It is hard to compete with that when your first gastronomic adventure of note with your Dad is the salad bar at the Ashford Harvester.

Rory is cozy. In an age of plastic, sepia filters and super-slenders, he is an aggregation of misty moors, mossy cairns, tartan rags, Peshawari caps, creaking mahogany desks, Pashto calligraphy, grubby raincoats and impassioned defenses of Hedgehogs. He is a beneficiary of the Posh turn, the post-GFC phenomenon where the brutish metropolitanism of the Brown years contracted into the sticky yokelism of the ‘Big Society,’ the Great British bake-off, the 2012 Olympics and schmalzy dramas like the King’s Speech.

He has the descriptive panache of JK Rowling. He talks about sharing a humble Christmas pudding with his mother in a remote cottage after being denied a holiday with the rest of his family due to ministerial commitments. Upon being besieged in some far-flung Middle Eastern compound, he keeps morale up by handing out oatcakes, combining the invented stiff upper lip of late Imperial Britain with the biccy-chomping of a Macmillan coffee morning.

There are indications Stewart is not entirely happy with being a talking head. By contrast, his co-host Campbell is a true media darling who loves nothing more than to hobnob with Gary Lineker or recall his encounters with Diego Maradona. As successful as “TRIP” has been, it is hard not to see it as a final destination for Rory rather than a springboard for a rejuvenated figure who still yet has a mark to make.

This is something of a shame. Despite my sceptism towards the “sensible centre,” Stewart’s memoir is enthralling and relatable. While it is tempting to chortle at the man’s more supercilious moments, he does show genuine reflection and contrition at his failings. He deserves our attention.

Rory and Afghanistan

The most noble aspect of Rory’s memoirs is his opposition to the surge in Afghanistan and his honesty in admitting the operation was failing early on. He is suitably contrite about the folly of Iraq. He comes in for abuse and scorn from pompous MPs and military officials who refuse to acknowledge the problems. While he cannot conclude that we should just withdraw, he at least chooses not to lie to himself about bringing liberalism to Kabul. While still obsessive about Britain’s moral leadership on the world stage, Rory is wise to the silliness of Britain’s outsized foreign policy ambitions.

One part of Stewart’s character is his heartfelt Islamophilia and love of peasant life in central Asia. Though I am not particularly attached to or invested in the culture or region, his enthusiasm is genuine and captivating. He speaks warmly of the adventures and the locals he meets, including the ones who tried to shoot him.

His work placement as a latter-day viceroy in Iraq has understandably made him wary of the arrogance of many Western foreign policy elites. This did not lead him to question the benefits of engagement with the Muslim world but rather to try to preserve authentic Afghanistan. To this end, he set up a charitable operation in the Kabul district of Murad Khane. His ‘small charity’ in Kabul had been funded by the then Prince of Wales, who apparently is also fascinated by Afghan calligraphy and woodwork. He talks of supporting traditional craftsmen and women and how fulfilling this work was. I don’t know if this account is an alibi for secret service work, but his love of the Afghans is genuine.

While working in Murad Khane, he contrasts his support for local tradition with the mayor’s ‘East-German’ stylistic tastes. Ironically, the imperial statesman is setting himself up as the preserver of tradition against the modernizing tendencies of native elites.

Stewart finds plenty in Afghanistan he would like to emulate in Britain. He even says he was attracted to the Conservative Party because Cameron’s ‘Big Society’ reminded him of his charity’s work. If tribe-jostling localism works in Murad Khane, it can work in Britain.

On the one hand, he hates notions of civilizing this noble peasantry; on the other, he can’t help but remark on the peculiarities of pre-industrial life. He seems to enjoy highlighting the alien anti-modernity of Afghanistan:

“ I was delayed by long, intricate greetings from the blacksmith and the man who fried goat’s brains”.

This might be orientalism, but it is orientalism in defiance of Western modernity and one that longs for the adventure and romance of the past. With all its dysfunction and backwardness, Stewart finds the East more real and virtuous than his fellow Westerners.

The disproportionate fascination Stewart, King Charles, and British elites throughout the centuries have had for the Muslim world is, from a practical perspective, perhaps of limited utility. I can think of alternative anthropological obsessions that are more useful from the standpoint of British governance.

Someone who’d spent their career in Silicon Valley might help us avoid standoffs with tech companies over censorship. A close confidante of one of Germany's foremost industrial aristocrats might help cultivate better businessmen. A fixer for one of South Korea’s chaebols might help us build some indigenous industry.

Instead, Rory and fellow worldly politicians like Tom Tugendhadt are disproportionately ensconced in the culture and inner workings of a historically rich but relatively unproductive part of the world economy.

Enthusiasm for exotic but ultimately marginal cultures was typical in the days of the Empire and perhaps obscured us from the real lessons we had to learn. While Etonians lost themselves in Sanskrit, the Germans and Americans studied Birmingham and Sheffield. British imperialists knew more about their subjects than their equivalents in Rome ever bothered to know about the Helvetti or the Garamantes, but it did them precious little good.

Besides the admirable ability of its residents to breed and resist centralized government, what does the Khyber Pass have to teach the British elite other than never to go there? Not so for Stewart. Afghanistan is good because its dysfunction requires compromise. This is the basis for his conservatism.

Rory the Tory

Rory’s allegiance to the Tory party has always seemed tenuous.

He discovered early on during the Cameron years that the Tory party rewards frivolousness and adaptability and obsesses over media instead of policy. He worries early on during the Coalition that the party of Churchill has become the party of Bertie Wooster. This suggests his contemporary recoiling from the party is not from recent revelation. For someone whose argument is “politics is not what you think,” he seems to have learned quite early on during his tenure that big ideas, conviction, and ideological vigor are not selected for at CCHQ.

Stewart is something of an oddball in Toryland, but his winning the candidacy for Penrith was, by his own admission, built on opposing the development of a supermarket (fairly conventional among local Tory gripes). While not necessarily typical, Stewart is finely attuned to the niceties and rituals of the established parties, government departments, think tanks, and the media. He is not so much an outsider as a regretful insider.

So, having left the Tories in 2019, what does he propose? He believes in a party in and of the centre.

The modern Tory party is, in reality, most of these things. It has kept its ideological commitment to Net Zero. It congratulates itself on its diverse cabinet. It claims to be fiscally responsible but isn’t tightening the belts of pensioners any time soon. It's also incredibly liberal. To this day, Cameron says one of his proudest accomplishments was gay marriage, a policy that would inevitably have gone through under Labour.

Rory’s centrist tribe is not out in the wilderness but rather is in the ascendancy on matters of process. If it feels marginalized, it is not because of “populism” but because of reality. Rory’s gripes with the current cabinet are more attitudinal than ideological. If one-nation conservatives like Stewart feel lost, even when Jeremy Hunt is Chancellor, and Grant Shapps is Defence Secretary, maybe their gripe is coming to terms with a political reality that no longer enables their fantasies. Contrary to being sober assessors of the possible, they are trapped in sentimentality and refuse to manfully take the country’s predicament seriously.

For Stewart, centrism, and indeed the promise of compromise, is a statement of moral goodness more than a set of policies. Breaking bread is in and of itself a good thing. To Stewart, the value of compromise is just as relevant in the people of Britain as the disparate factions of Murad Khane. But over there, the ability to compromise is the only thing preventing outright intercommunal violence. In a modern country like Britain, can we not aspire to politics beyond petty tribal negotiations? Is the worthiness of parliamentary sovereignty and a common polity not that we can pursue great change without the threat of chaos?

Of course, Stewart’s idea of compromise is skewed leftwards. Like most ‘Burkean’ conservatives, he stands athwart history, muttering, “Gently.” When listening to him talk on intractable political challenges like the rising popularity of rightwing parties due to mass immigration in Europe, his remedy is little more than affirming how ‘serious’ we must be and that we need to understand people’s concerns, with no honest discussion about what actual decisions have to be made.

For Stewart, as for other exiled tories, the sensible conservative solution nowadays is not to take tough decisions but to “feel” and “understand” their way out of political battles they would rather see not fought.

Rory in Government

The most captivating part of the memoir is Stewart’s time in government, where he works in the department for international development (DFID), the foreign office, and as the minister for prisons. The passages could be mistaken for a right-wing critique of neoconservatism, liberal interventionism, Cameroonism, and the civil service. Stewart’s opposition to Johnson is well-documented but ultimately is crowded out by his more serious attack on the state of modern British elites.

He documents active disobedience from the civil service. They are not like Sir Humphrey, obsequious yet patronizing, but rather pull rank on him. When Stewart says he wants to speak regularly to heads of country offices, an official retorts, “You can understand why we might be worried that you could be using this department as your own ego trip.”

In another account, Stewart goes through a kafkaesque odyssey trying and failing to stop idiotic apparatchiks funding Jihadist-controlled municipal councils in Northern Syria. He is actively thwarted by officials, having to jet across America and back to London to discover he has no authority to veto the British state funding Islamists.

He finds similar opposition in prisons. When suggesting searching those entering prisons for drugs (a practice common in the U.S. and Sweden), he is accused of utopianism. Despite it being blindingly evident that narcotics are being transported in large quantities by officers into prisons, Stewart is opposed when trying to install scanners, whether it be because of union opposition, human rights law, or health risks.

He is told of great civil servants, titans of their field, like Michael Spurr, the former CEO of the prison service. But where he is promised princely mandarins, he finds vegetables, blaming all their problems on a lack of funding. This is confirmed by the recent Daniel Khalife escape, which was made easier because 40% of Wandsworth prison officers had not turned up to their shift.

A thousand city-states

This blistering critique of the British state could be an addendum to Dominic Cummings's “The Hollow Men.” Cummings sought to remake the state, but the lack of a significant cadre and the failures of his prime minister saw him fail. For Stewart, revolution is not an option.

The primary evil in Stewart’s world is the frivolousness and dysfunction of modern politics. In this sense, he is not so different from Dominic Cummings. But Stewart’s remedies revolve around the dissipation of power to the local level and the negation of strong executive leadership.

Rory’s chosen balm for soothing Britain’s deleterious state is more devolution, beyond the further expansion of local government power to the inertia of citizen’s assemblies, with plenty of references to “communities.” This is not a new insight. His passion for localism extends back to at least 2014.

This is, in effect, the same remedy he had for Murad Khane. In the same interview, he discusses separating the legislature from the executive, slashing the number of MPs from 650 to 100, introducing powerful locally elected mayors, and imposing greater transparency and controls on the security services. He wants American-level vetocracy.

But the appalling dysfunction of America’s system has been partially mitigated by other developments, including the building of an enormous imperial bureaucracy that is highly independent of legislative oversight. The U.S. is also unique for having a begrudging tolerance for eccentrics they fund to build things. American internet dominance was enabled by permissionless innovation, but such a cavalier attitude to technology would horrify Rory and the stakeholder yeomanry he seeks to enshrine.

U.S. economic divergence from Europe was partly due to fracking, an industry pushed through by provincial old boys. Stewart voted against any fracking industry in the UK. He idolizes the dysfunctional aspects of the American political system: its separation of powers and privileging of endless litigation. But he would reel in horror at a British Musk, Bezos, or George P. Mitchell.

Stewart’s view on British industry, for which this blog is known, is limited. His 2014 description of the British economy below provides a fragment from which one can perhaps deduce his ideal economic model.

From this, one can perhaps gauge that the more small and twee a job is, the more inclined Rory is to it. The notion of giant industrial conglomerates and huge factories does far less to inspire him than sporadic, busy work. Later in the memoir, he describes first entering the DEFRA HQ for his first cabinet position.

Of course, ICI was also known as one of the most profitable British industrial companies. It was not a laggard hiding its middling market share behind a Union Jack, but an actual, gigantic corporation before mismanagement led to its collapse in 2007. This wasn’t like a coal mine closing. It was the end of a real industrial expertise.

That a temple of machines had been substituted with a government department doesn’t irk Rory in the slightest. The transition from productive manufacturing to regulating, norm-setting, stakeholding, cross-pollinating, and ‘world-leading’ is as natural as the shift from hunter-gatherers to subsistence farmers.

No more Great Men

Rory’s relationship with great men is complicated and inevitably stems from his, it seems, excellent relationship with his distinguished father – the colonial officer, soldier, and spook Brian Stewart.

In Rory, we see no desire to break from his father’s legacy. To manfully follow in the footsteps of your acclaimed progenitor, likely knowing history and the state of the world will not permit you to match his accomplishments, is admirable and relatable to many Britons today.

Having trundled across Asia, you would imagine Stewart has idolized Macedonian basileis, steppe warlords, Mughal emperors, and Etonian nabobs. In his youth, he compared himself to Alexander. However, he has remarked that the modern world is too complex for great founders. This ignores the essence of such individuals: to create clarity out of chaos, empires out of fiefdoms, and institutions out of disparate interests.

Rory has previously been described as Lawrence of Belgravia. It is alleged that Cameron referred to him as a modern-day Julien Amery. Amery, however, was a buccaneer who held on to the British Empire and withered away with its fall.

Perhaps it would be more appropriate, if controversial, to compare Stewart with Enoch Powell. Powell was the last Victorian, a man of humble beginnings who gained prominence academically, excelled in the Second World War, rising from private to brigadier, and subsequently entered politics. But he could only understand a world with Britain being powerful, independent of international order and the U.S., which he hated. Faced with the nation’s downward trajectory, he chose the political equivalent of self-immolation.

Stewart was never caught up in great battles; he had to seek out hipsterish adventures in far-flung parts of the world but was never quite given the chance to show his quality. Stewart’s quibbles for Britain are different from Powell’s, but faced with a similar level of despair, he opts to flourish as an observer of decline.

But while his hearth is secure, there is the distinct sense Rory is not entirely happy with his current lot. He calls his own podcast trivial. While he is grateful to have an audience he can vent to over Boris, he does seem to tire of being the pet-tory whose great virtue to liberals is his harmlessness.

But any desire to revitalize his prospects as a world-changer is constrained by his political posture. Britain doesn’t need more devolution, compromise, or respect for the process of government. It needs a new elite. This is the obvious conclusion of Stewart’s memoir. But rather than commandeer the ship of the state and scour the barnacles that weigh it down, he would disassemble it into a flotilla. While Hobbes’ state is a Leviathan, Stewart’s is a Hecatoncheires, a hundred writhing hands clamouring to have their say.

And with that, Politics on the Edge is a wreath being laid down to honour a most peculiar career, rather than a portent to a political return. Despite this, I would recommend it to all and came away liking Stewart a great deal more than when I started. His wrongheadedness aside, he will stand for decades as one of our country’s most likable commentators. For a man of clear privilege, he has a relatable vulnerability that transcends class boundaries and speaks to all our fears about decline and failure. It will fall to others to turn this common angst into action.

A brilliant article, which also saves me from having to read the book. An aside; Rory was known, from hospital days in Iraq (I am reliably informed) as 'Florence' of Belgravia. This was, allegedly, due to his insistence that being overly nice to Jihadis would stop them planting roadside IEDs and such.

In this, as with so many other things, Florence was wrong.

Great read Rian.