Start the Presses

Heavy forge presses seperate real industrial powers from pretenders. They are also critical to the nuclear industry. After years of limited investment, the British state has one.

One of the essential criteria for an advanced industrial society is access to a heavy forging press. Many are familiar with hydraulic presses crushing sweets and watermelons. Heavy forging presses are identical as a concept, but are the size of a 10-story building. Large hydraulic presses were initially demonstrated in 1646 by the French polymath Blaise Pascal. They were first incorporated into industrial processes by the English inventor Joseph Bramah in the late 18th century. Since then, these presses have grown to enormous proportions. Today, they are essential to the manufacture of big machines, including cars, aircraft, tanks, oil platforms, and reactor pressure vessels for nuclear plants.

Forge presses compress material, increasing its strength-to-weight ratio, while also reducing metallurgical defects. This allows for the mass production of large components made up of light metals like magnesium, aluminum, and titanium, as well as high-quality steel. This is essential to aircraft, spacecraft, tanks, pressure vessels and most machines requiring a high standard of structural integrity.

If lighter materials like aluminum, magnesium, and titanium can be forged into larger components, this translates into performance. This is why large jet aircraft became economical to make, and why at least 25% of an F-35 fighter’s weight is titanium. It is essentially like replacing Lego with Playmobil. Rather than building a system out of many parts, meaning increased weight and less strength, you build it out of a smaller number of larger, stronger parts.

Presses also greatly increase the speed of the manufacturing process and make building advanced systems possible with fewer man-hours. If you want to be an industrial powerhouse or have an effective military-industrial complex, you need heavy forging presses. Only a few powers have such capabilities, including the USA, Britain, the EU, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Russia, with legacy capabilities existing in South Africa and Ukraine.

Press power is airpower

The importance of heavy forge presses became clear in the aftermath of World War 2. Germany, during the run-up to the war, suffered from shortages in aluminum, but had bountiful supplies of magnesium, a material one-third lighter. But it was also prone to rupture under the strain of heavy hammers. To utilize magnesium for aircraft, German industry built a 33,000-ton (U.S. short-ton) heavy die press located in an IG Farben facility in Bitterfeld. The 33,000 tons refers to the force that can be exerted rather than the weight of the press itself.

With this, Germany was able to manufacture innovative aircraft with limited material supplies, most notably the Messermischmit 262 jet fighter.

After the war was over, U.S. and Soviet industrial experts sought to capture this knowledge and apply it to their industries. The Soviets simply took the largest press from Bitterfeld. The U.S. dismantled two smaller presses and shipped them back home as reparations.

The U.S. government subsequently undertook the heavy press program. The air force led the procurement of 4 forging presses and 6 extrusion presses. The difference between forging and extrusion presses is fairly simple. A forging press is slowly placed down on a material which is essentially squished into a die cast of the desired shape. The largest forging press today is owned by the Chinese Erzhong Group and can exert a downward force of 80,000 tons on any given metal. An extrusion press meanwhile pushes metal through an orifice to create a certain shape.

The heavy press program cost $235 million when completed in 1957, or around $2.6 billion today.

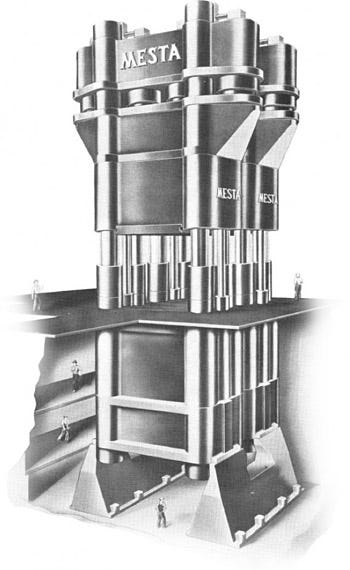

Picture 1: A 50,000 ton hydraulic forge press, built in 1954 by the Mesta Machine Company for the U.S. Air Force, Source.

These heavy presses are powered through hydraulic systems, and can last a long time. Universal Alloy Corporation (UAC) is a U.S. company. In 2005 it bought a German-made extrusion press from another U.S. supplier. This machine had originally been built in the 1940s to service the Luftwaffe, before being seized by the U.S. as a form of reparations. It is still functioning today.

This is also true for a large number of U.S. forges built by the press program. The majority are still working and are expected to for decades to come. Arconic, a U.S. aluminum manufacturer recently bought by private equity firm Apollo, uses a 50,000-ton forge from the Fifties to make parts for the F-35 program.

Amongst the newer additions to U.S. forging is a 60,000-ton press supplied by the German SMS Group to California-based Weber Materials, a subsidiary of the German manufacturer Otto Fuchs. This was supplied in 2018 and is focused on the aerospace sector.

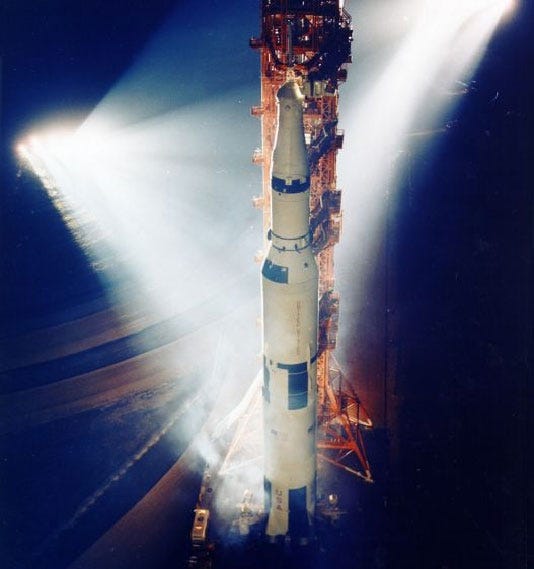

These presses were initially designed to supply the military. Arconic’s precursor, Alcoa, had operated Mesta’s 50,000-ton press as a contractor for the U.S. government before buying it outright in 1982. Alcoa was also essential for forging the aluminum parts used in the construction of the Saturn V rocket. But they also greatly facilitated the commercialization of air travel. Airbus and Boeing, as well as Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, rely on these presses to manufacture their airframes.

Picture 2: Saturn V launch vehicle, Source.

Without the $2.6 billion investment in heavy presses, the U.S. aerospace industry, tallying up revenues of $741 billion in 2022, would not have been possible.

The market for reactor pressure vessels

Forging presses are not just valuable for aircraft. They are also needed to make reactor pressure vessels (RPVs), the containers of the fission process within most nuclear power plants. While aircraft require the forging of lighter metals and steel alloys, RPVs are built from various grades of high-quality steel.

While presses targeted for lightweight metals like aluminum and titanium demand a heavier press (over 50,000 tons), presses designed for high-quality steel components like RPVs need less force (under 20,000 tons) but need to be able to forge larger ingots, with 350 tons generally being the minimum.

RPVs are enormous and require heavy presses. For example, the European Pressurized Reactor (EPR) is 573 tons when being transported. The advanced boiling water reactor (ABWR), licensed by General Electric and developed by the Japanese nuclear industry, has a weight of 890 tons.

An RPV is not one slab of steel, but is built from a series of components, which can involve multiple partners. For example, Britain’s Sizewell B pressure vessel was partially built by French Le Crusot, Japan Steel Works, and Kobe Steel Corporation.

Whether a country has immediate access to a heavy forge press can affect its civil nuclear power strategy. For example, Canada’s nuclear program was built around creating a design that did not require heavy forging presses for the pressure vessel, as this was a capability Canada did not have. As a result, Canadian heavy water reactors (known as CANDUs) have their own, almost entirely domestic supply chain.

The U.S. forge presses are primarily geared toward aluminum, titanium, and steel superalloys for aerospace needs, rather than for RPVs. Expertise in forging one metal does not necessarily translate into another. In fact, only a few companies can make RPVs. As recently as 2008, Japan Steel Works was the only corporation that could make castings for heavier RPVs. This has changed recently. In 2021, this was the estimated global capacity for RPVs.

Figure 1: Major forge presses for nuclear reactor pressure vessels in 2021, Source.

This amounts to 42 RPVs potentially being built annually. This has increased markedly in recent years. In 2008, the global capacity was just 15 per annum. The main increase in capacity has come from China and South Korea’s Doosan. The Russian capability is a hangover from the Soviets, whose largest presses exceeded the U.S. in their maximum force.

Mishaps at Le Creusot forge

France theoretically has RPV manufacturing capability through a forge at Le Creusot, but it has struggled with engineering failings centered around the Flamanville nuclear plant project.

This project was started in 2007 and hopes to end in 2024, after 12 years of delays. The project has been an unmitigated disaster for many reasons, with analyses suggesting a project manager was not assigned by EDF to the program until 2015. But the most serious single issue was the discovery of a high concentration of carbon in the top dome of the pressure vessel. This potentially ruins its structural integrity.

This was discovered after the 500-tonne steel container had been installed. This delayed plant construction for years and led to the forge suspending work for 3 years between 2015 and 2018. While it survived the controversy, replacement parts that have been mandated by the French nuclear regulator will be sourced from Japan Steel Works. Nuclear power is used as a tool to demonstrate the country’s engineering excellence, but the Flamanville fiasco has done the opposite, and provided considerable ammunition to antinuclear activists.

Japan Steel Works (JSW), for their part, are a British Weeb’s dream. They were initially set up with the financial aid of British firms Vickers and Armstrong Whitworth. They manufactured the guns of the Yamato battleship during the war, and to this day still manufacture a handful of Samurai swords. In 2010, they had an 80% of new RPV orders, but have seen this monopoly shrink as Russia, China, and South Korea dominate new builds.

Picture 3: Japan Steel Works 14,000 tonne forge press for nuclear components, Source.

Unsurprisingly, China’s capacity has grown markedly in recent years. This is in line with their nuclear ambitions. The country’s nuclear champion CGN signed a deal with EDF to build its reactors at a plant in Taishan. But unlike in Flamanville, the first plant had an RPV built in Japan, and the second RPV was entirely manufactured in China. The country also developed the capacity to build RPVs for Westinghouse reactors through technology transfer agreements.

The simple business of pressing steel into large ingots for reactor vessels is in fact a highly exclusive tradition of knowledge limited to a handful of corporations.

Sheiffield Forgemasters

And what of Britain’s capabilities?

In fact, the British government owns its own heavy forging press. Sheffield Forgemasters traces its origins back to the 1800s. It was nationalized by the government in 2021 and is critical not just for forging components for the Royal Navy’s submarine program, but also for pressure vessels used to house Rolls-Royce’s naval nuclear reactors and the company’s prospective small modular reactors (SMRs). Beyond the defense sector, Forgemasters has provided ultra-large castings that are used to build heavy forge presses, including those of the SMS Group.

Aside from its press, it has demonstrated an ability to develop innovative techniques like electric beam welding (EBW). It even has a ‘fun’ story of manufacturing a giant gun for Saddam Hussein, which customs seized at Teesport dockyard in 1990.

Forgemasters was not nationalized because it was unprofitable or poorly run. Within a year of nationalization, its revenue had grown from £80 million to £130 million. Rather, its orders were limited primarily to defense contracts, and so it could not invest in new forging press to keep up with demands.

The government, upon buying the asset, spent £120 million on a 13,000-tonne forging press then owned by Mitsubishi Nagasaki Industry. This is the largest piece of a $400 million investment into the forge. The new press itself weighs 8,000 tonnes and took 81 days to load, travel by ship to Hull and unload. This is an upgrade on an older 10,000-tonne press, which could make ingots weighing a maximum of 350 tonnes. This is enough to manufacture components for nuclear reactors, but not the largest sections of the pressure vessel.

The nationalization was necessary, but in hindsight looks like a failure of preemptive government action.

In 2008, Forgemasters had the capacity to manufacture 40% of nuclear components. Because of this capability, the forge had a partnership with U.S. reactor supplier Westinghouse, specifically to forge pumps for its latest AP 1000 design, and for designs that license Westinghouse technology abroad. This means Sheffield-pressed steel has actually found its way into Chinese nuclear plants.

In 2010, the forge planned to upgrade its operations with a new 15,000-tonne press, allowing it to not just build pumps for Westinghouse, but its RPV as well. Westinghouse was receptive to this, since at the time they could only rely on the Japanese, who were fully booked. The Labour government in 2010 provided Forgemasters with an £80 million loan to buy the press. But this was canceled in the early days of the coalition government, on the basis that it should be financed by financial markets.

Picture 4: Sheffield Forgemasters

Now, 2010 was obviously a financially stressful time for the UK. But as we found out in 2021, Forgemasters is a strategically important asset no government could allow to fail. It needed to be upgraded just to keep our defense industrial base up to standard, and potentially open up a valuable export market. While the Forgemasters loan was scrapped, the much larger aid budget was ringfenced and even prioritized. It is therefore hard to justify the decision on the grounds of financial prudence. Rather than investing £80 million in 2010 for a 15,000-tonne press, the government has found itself paying £400 million for a 13,000-tonne press in 2021.

Since then, the primary partner for Westinghouse on RPVs has been South Korea’s Doosan. Despite going bankrupt in 2017, Westinghouse is alive as a nuclear developer, is currently licensing the technology to South Korea and China, and is planning to export more reactors to Eastern Europe. Three AP 1000 reactors are being built in Poland. This could lead to more orders to Czechia, Romania, Slovakia, and Ukraine. This is being helped by the U.S. government through aid and its export-import bank. In a different world, this could have been a significant windfall for Sheffield Forgemasters. Instead, the beneficiary is likely to be Doosan.

With a new 13,000-tonne press, Forgemasters is well-placed to build pressure vessels for small modular reactors (SMRs), especially those being designed by Rolls-Royce. This market opportunity is exciting but nascent, and under current government plans, a decision for which SMR the UK government backs will not come until 2029. Meanwhile, competitors like Korean Doosan have been able to invest in SMR companies and are already manufacturing components for them.

As a nationalized company, Forgemasters will get its upgrade and could perform very well due to rising interest both in reactors and rearmament. Depending on its success, this could be a blueprint for more state-owned corporations in Britain. But ultimately, the delay in investment of 11 years has left Britain well behind other countries in terms of supplying large RPVs.

A lesson here is that preemptive investments, even subsidies, are often preferable to waiting for a strategic asset to run out of funds, at which point a hurried government buyout is the only option.

Despite the relative decline in heavy industry’s importance from a macroeconomic perspective, it remains critical in the world of great power politics. When it comes to hard power and the ability to build big, complex systems, the possession of just a handful of heavy forges separates the real powers from the multitude. British policymakers should consider this lesson as it applies to the wider economy.

The coalition was a disaster.

Very good article.