Ineos: The petrochemical empire of Britain’s last industrialist

Jim Ratcliffe is Britain’s most prominent industrial magnate and the largest shareholder in a sprawling chemical enterprise. Exasperated by Britain's industrial decline, he is building elsewhere.

With revenues of £55 billion in 2022, Ineos is Britain’s most significant private corporation and the sixth-largest chemical company in the world. A trio of founders governs it: the accountant John Reece is the chief financial officer, the former British Petroleum engineer Andy Currie is the CEO, and Sir Jim Ratcliffe is the founder, chairman, and largest shareholder.

Established in 1998, Ratcliffe’s Ineos is an oddity in modern British commerce. While the economy shed manufacturing jobs and wound down production in the North Sea, and global chemical production drifted inexorably to China, Ratcliffe duly collected unwanted British, European, and American chemical and petroleum assets with debt. Sir Jim has consolidated these unfashionable businesses into one of Britain’s most successful companies. The company is sprawling, with over a hundred manufacturing sites and thirteen research centers globally, including four chemical plants in Britain spread between East Yorkshire, the North West, and the North East.

The company’s scope is enormous, with a presence across the entirety of the oil and gas supply chain, from extraction and refineries to petrochemicals and specialty chemicals. The official organization chart splits the corporation between joint ventures, holding companies, divisions, and various consumer and sports brands.

Ineos corporate chart , Blue = holding company, Yellow = division, Red = consumer & sport, Turquoise = joint ventures, Source: Ineos 2022 sustainability report

I have simplified this sprawling mess into a more basic overview below. In simple terms, Ineos is 65% a chemical producer, has a smaller fossil production and refining business, and dabbles in consumer brands and sports.

Simplified corporate chart of the Ineos corporation with 2022 revenues, Source: Ineos annual report 2023

There are three primary business groups. “Group Holdings” is the primary petrochemicals division. “Quattro” is the bulk chemical division focused on aromatics, styrenics, and acetyls. Aromatics are benzene-heavy chemicals. Styrenics are essential synthetic rubber and plastics. Acetyls are used as fibers in clothing, food preservation, and pharmaceuticals, among other things.

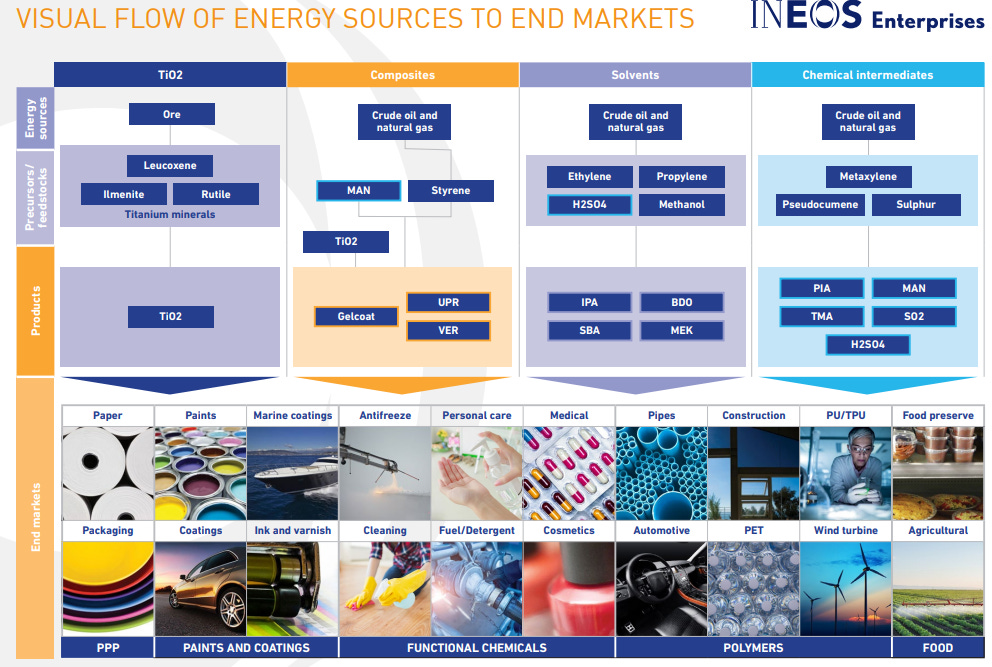

“Enterprises” is the division that manufactures specialty chemicals like titanium dioxide (paints), solvents, and coatings. Confusingly, “Enterprises” also produce chemical intermediates like sulfur dioxide (essential for paper), purified isophthalic acid (plastics), trimellitic anhydride (resins), and maleic anhydride (cosmetics).

Besides these companies is the “Energy” division, which owns oil and gas assets in the North Sea and thousands of wells in the Eagle Ford shale basin in Texas. Ineos also has a 50:50 joint venture with PetroChina called PetroIneos, which manages two major refineries to produce fuels and feedstocks for its petrochemical business. Through a debt-fuelled acquisition strategy, it has garnered a presence throughout the entirety of the chemical supply chain, from the extraction of crude oil to the refinement of consumer products.

The different businesses

Ineos Holdings, the largest leg of the business, had revenues of £18 billion in 2022. It contains three main businesses: the olefins and polymer assets in North America and Europe and the chemical intermediates business. This business is concerned with refining crude oil and gas into petrochemicals. Ineos refines these from petroleum feedstocks like naphtha, ethane, butane, and propane, refined from crude oil and natural gas.

Holding’s most popular petrochemical is ethylene, which accounts for one-third of the global production of primary petrochemicals. It is the critical building block to produce many higher-value-added chemicals, including polyethylene, a standard commodity plastic. Other key Ineos petrochemicals include butadiene and benzene. Intermediates are chemicals refined from primary chemicals like ethylene. One such intermediate is phenol, a key ingredient in synthesizing plastics, for which Ineos is the largest producer in the world.

Ineos Group business, Source: Ineos Sustainability Report 2022

Ethylene and propylene are the most critical petrochemicals for this segment, as they can be further refined into polymers like polyethylene and polypropylene. These are turned into plastic products like films, filaments, pipes, and coatings. Butadiene is critical to developing synthetic rubbers, and benzene derivatives like phenol are needed to manufacture resins and synthetic fibers like nylon.

Ineos Quattro's revenue was £15 billion in 2022. This business takes petrochemicals and creates specialty chemicals. Its segments include Styrolution, which manufactures styrenics. Another business, INOVYN, produces polyvinyl chloride (PVC), epichlorohydrin (ECH), caustic soda, and chlorine. The aromatics business manufactures paraxylene (PX) and purified terephthalic acid (PTA).

Ineos has incorporated these businesses in a patchwork fashion. For example, Styrolution, initiated in 2011, was a joint venture with the German chemical giant BASF before Ineos bought all the shares. INOVYN was a joint venture with the Belgian chemical producer Solvay, which exited in 2016. The aromatics and acetyls business came from purchasing the chemical business of British Petroleum’s chemicals business, which had built it up by acquiring assets from the U.S. chemical firm Amoco.

Quattro business - bulk chemical division, Source: Ineos

Ineos Enterprises is a smaller business, totaling £2.5 billion. This business primarily sells specialty chemical products, including a titanium dioxide pigment business centered around North America. Titanium dioxide, a whitening pigment used primarily in paints, was one of the primary money-makers for the U.S. chemical giant DuPont. Chinese companies muscled in and dominated global production.

Chemours, a successor to the DuPont Corporation, dominates the U.S. titanium dioxide market, while Ineos has a respectable 14% share. The two other significant segments of the Enterprises business are solvents, composites, and chemical intermediates like sulfur dioxide. After the Chinese chemical producer Jiangsu Zhengdan, Ineos is the largest producer of trimellitic anhydride, a curing agent used in paints, plastics, and resins.

Enterprises business - Speciality chemical division, Source: Ineos

Ineos has a 50:50 joint venture with the enormous Chinese oil & gas company PetroChina, referred to as PetroIneos. This company owns and operates the Grangemouth refinery in Scotland and the Lavera refinery in France. These refineries have a combined refining capacity of 360,000 barrels per day, compared to the roughly 1.3 million bpd capacity of the UK. The Grangemouth facility is fed oil from the North Sea via the Forties pipeline. Set up in 1924, it has historically been Britain’s single-largest refinery. After years of union disputes, decreased jet fuel and gasoline demand, and the lack of new oil and gas licenses in the North Sea, it is being significantly downscaled and turned into a storage facility.

Ineos invests in consumer brands like the Grenadier 4X4 and the Belstaff fashion brand. It also has sports assets, including being a minority shareholder in the Mercedes-AMG Petronas Formula One team. Then there is Ratcliffe’s 28% stake in Manchester United and outright ownership of OGC Nice. Manchester United, the second most valuable football club after Real Madrid, is owned by the U.S.-based Glazer family and has gone over ten years without winning their domestic league. Ratcliffe is now a rare British presence in a league dominated by U.S. and Arab owners.

Ratcliffe’s amalgamation of unwanted petroleum and chemical assets has been a bright spot in a decades-long structural decline in these industries in Britain, Europe, and the US.. The decline in Western chemical manufacturing has been mainly due to the enormous increase in supply established in China, which will manufacture half the world’s chemicals by 2030. From petrochemicals to Teflon to titanium dioxide, Chinese chemical abundance, assisted by generous government subsidies, has led Western oil majors and chemical companies to divest heavily from their less profitable businesses.

DuPont, once the largest chemical company in the world, has divested its most controversial and pollutive industries into the distressed company Chemours and has become a much smaller producer of specialty chemicals for water treatment, protective clothing, and electronics. This was down partly due to litigation but also due to a glut in Chinese capacity.

China’s modern dominance of the chemical supply chain. Source: CEFIC.

Ethane by Sea

One of Ratcliffe’s recent tour de forces was a $2 billion investment in eight tankers to carry ethane, a byproduct of U.S. fracking, from the company’s Texas shale fields to Europe as a petrochemical feedstock. These “Dragon ships” were manufactured in Shanghai by state-owned Sinopacific Offshore and Engineering. The ships transport ethane continuously from the U.S. to Ineos assets in Europe, principally Grangemouth, the Rafnes petrochemical complex in Norway, and an olefin production complex in Antwerp.

While the Dragon ships feed Europe, another eight Chinese-manufactured “Very Large ethane carriers” (VLECs) have been built to transport ethane from the U.S. to East Asian customers. By 2026, the company will have ten VLECs and eight Dragon-class ships, making it the world’s largest ethane carrier fleet.

The Dragon ships have a capacity of 27,500 cubic meters, while the VLECs have a capacity of 99,000 cubic meters, meaning currently, a total capacity of 1.2 million cubic meters of ethane. U.S. ethane production has exploded to 2.6 million barrels per day since the fracking boom, or roughly 152 million cubic meters annually. Assuming the fleet could make around twenty trips on average a year, it can transport upward of 22 million cubic meters annually. The seaborne ethane trade barely existed before 2016, but Ineos has positioned itself as the primary carrier.

In 2023, the company also chartered two large Korean-built liquified natural gas (LNG) carriers to transport its output in Texas to an as-of-yet uncompleted regasification terminal in Brunsbuttel, Germany. The 20-year deal gives Ineos 1.4 million tons per annum of capacity at the terminal, a small fraction of the 57 million tons of natural gas consumed by Germany in 2021. The company’s LNG shipping business looks set to expand as Europe secures long-term alternatives to cheap Russian gas.

Britain’s last Industrialist

Ratcliffe is a rare figure in modern British life. He made his name in the dour world of chemicals as the rest of the country became ensconced in the creative sector, Tech, and the post-industrial economy. Sir Jim is an openly middle-brow, buccaneering provincial who enjoys football, big off-roaders, cycling, sailing, running, and pints at the Grenadier pub. His background, industry, and demeanor are a novelty in an increasingly managerial culture.

Initially trained as a chemical engineer, he transitioned into accounting. He is relatively open about not having a comprehensive knowledge of his entire chemical industry. Upon buying the Grangemouth refinery in 2005, he had yet to learn how refineries worked. He instead relied on consultant and Shell veteran Jim Dawson to fill in the blanks.

Ineos operates on a federated business model run by Ineos Capital, which refers to the central management team. The three older gents who run it do not direct the company from the top down, often focusing on their pet projects as much as the fundamentals of the business. Individual business leaders run their operations independently and only meet the senior management once a month for a check-in.

Ratcliffe has affirmed that Ineos will remain a private enterprise, never entertaining the possibility of going public. The rationale is clear. Different chemicals have different financial profiles, with some having higher margins and some going through more volatile business cycles. Ineos is a collection of businesses that cannot be easily categorized as growth, value, or cyclical stocks. If it were to be listed, it would likely face the same attacks from activist investors that rocked DuPont and Dow Chemical.

In straightforward terms, the venerable DuPont and Dow Chemical Company were tactically merged and subsequently split into three separate companies, with each new company focusing on a particular group of chemicals. Investors also forced DuPont to divest its fluorspar and titanium dioxide business into a new company, Chemours, in 2015. This investor-led form of economic rationalization has turned DuPont from the largest chemical company in the world in 2000 to a marginal player with poor shareholder returns.

Fear of listing in London is also not unjustified. Just as Ineos was getting started, two prominent British industrial conglomerates, General Electric Company and Imperial Chemical Industries, were destroying themselves through poor decision-making, disastrous acquisitions, and unnecessary divestments incurred from shareholder pressure. Ineos's initial expansion depended on buying ICI's unwanted chemical business in 2001.

Ratcliffe, alongside Anthony Bamford of the heavy equipment manufacturer JCB and home appliance mogul James Dyson, formed a high-profile industrial trio supporting the Brexit referendum. Ratcliffe’s frustration with the European Union was partly based on environmental regulations. Europe may have employees in the petroleum industry, but it does not have a petro-elite. While Europe potentially has significant reserves of gas and oil that can be recovered through fracking, an effective ban by national governments has rendered such a prospect null and void.

But post-Brexit, Britain’s outgoing Conservative government has left Ratcliffe banging his head against a brick wall. Since 2015, he has noted Ineos makes next to no money from its British facilities. More recently, the chemical magnate has called government energy policy “crap” while calling for more nuclear power and ending the moratorium on onshore fracking. He believes that permissive government attitudes to energy production lower manufacturing costs, and Net Zero obstructs this. He has also criticized the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), which blocked his takeover of Swiss rival Sika’s concrete additives business. In the run-up to the recent election, he even chastised the Tory Party for breaking its post-Brexit promises on immigration.

But despite his complaints and occasional interventions, Ratcliffe has not built a power base from which to assert his views onto Britain’s main decision-makers. Aaron Banks, who principally made his relatively modest £50 million fortune through insurance companies, has been far more direct in his political support, seriously hurting the Conservative Party in the recent election by funding the insurgent Reform UK.

Ratcliffe’s political instincts are adjacent to the standard Tory free market right but far from identical. He is adamant that the country’s manufacturing base needs to be prioritized, even at the expense of comparative advantage. He laments the gap in productivity between the South East and the North. While not articulated explicitly, it hints at an economic platform that is more libertarian on energy and regulation while less cavalier on immigration and the prioritization of services. It is a potentially popular position that has not recently been articulated in British policymaking.

Downcast about Britain’s future, Ratcliffe traverses between his North European industrial empire and his boats tied up in Monaco. Despite being 71, he has remained physically able, with no signs of contemplating retirement. With no known succession and his attention being eaten up by Manchester United, Ratcliffe may be Britain’s last genuinely significant Titan of industry. Aspiring British corporate giants, from the semiconductor company Arm to defense manufacturer Meggitt, are being bought by foreign investors, usually Americans. Meanwhile, established British manufacturers like Rolls-Royce, BAE, or Unilever are functional, publicly traded dead players. With industrial electricity prices at near-record highs and likely to not come down as long as our current Net Zero strategy remains, the future of British industry is not encouraging.

Ratcliffe may have to begin institution-building if he does not want to be our last industrialist. This could involve funding research papers or turning marginal, largely powerless associations like the Energy Intensive Users Group into a significant interest group through patronage and funding. Given the institutional weakness of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), there is space for this, but sponsoring such an initiative would be a thankless task, with any potential payoff measured in years.

Today, Ineos is looking to extend its operations further in North America and detach its fortunes from a stagnant British industrial base. Reversing such a decline would take years of hard work and face considerable opposition from multiple sources, from environmentalists to Nimbys to the Financial Times and the Economist. While counter-declinists would be delighted to see Sir Jim dedicate his hard-earned cash to funding a new consensus on the importance of industry, one might wait in hope rather than expectation.