Europe, not China, could become a casualty of U.S. industrial policy

America's reshoring initiative will likely not hurt China, but could lead to a sustained backlash in Europe.

In early August, the German government announced a €10 billion investment into a new Dresden-based fabrication plant led by the Taiwanese semiconductor fabricator TSMC, which will provide around €3.5 billion of the funding.

This was hailed by European leaders as a declaration of confidence in the continent’s industrial base, even if it required €5 billion in German state aid to convince TSMC. This plant will not be online until 2027 and will not manufacture today’s most advanced chips, which remain limited to Taiwanese factories.

Instead, it will be fabricating chips that were cutting edge in 2013. By the time the plant comes online, it will be 14 years behind the state-of-the-art.

The structure of the deal is notable as well. Despite fronting up a minority of investment, TSMC will get 70% equity in the plant. Such lopsided deals make me somewhat relieved the British semiconductor strategy was next to nothing. If Germany had to bribe TSMC to make investments, the British government would be over a barrel.

This European deal is dwarfed by TSMC’s $40 billion U.S. investment in a series of fabrication facilities in Phoenix, Arizona. There they will be fabricating today’s most advanced N3 chips. But by the time they are built, Taiwanese facilities will be fabricating more advanced N2 chips.

TSMC is hoping to receive $15 billion from the U.S. government to build these fabs. While Europe struggles to match U.S. subsidies for semiconductor companies, its position in the future of the industry is increasingly marginal. While the U.S. is home to 60% of private sector R&D investment in semiconductors, for the EU it is 6%.

The U.S., as part of a stimulus to post-Covid economic woes and the threat of China, has unleashed significant subsidies to jumpstart its industrial base. This is primarily focused on the ‘green’ transition. But it is also geared towards semiconductors. The result has been a massive expansion in U.S. manufacturing investment, localized around semiconductors and electronics.

But this is not particularly hurting Chinese manufacturing or preventing Chinese entities from acquiring high-end technology. U.S. restrictions on the supply of high-end graphics cards and semiconductors to China appear not to be working and have been opposed by key captains of American industry, from Nvidia’s Jensen Huang to the CEO of Raytheon.

Despite U.S. restrictions on 5G chips, Huawei has managed to overcome them and make its own. The Chinese industrial base is as of 2022 more automated than the U.S., with a higher robot-to-worker ratio.

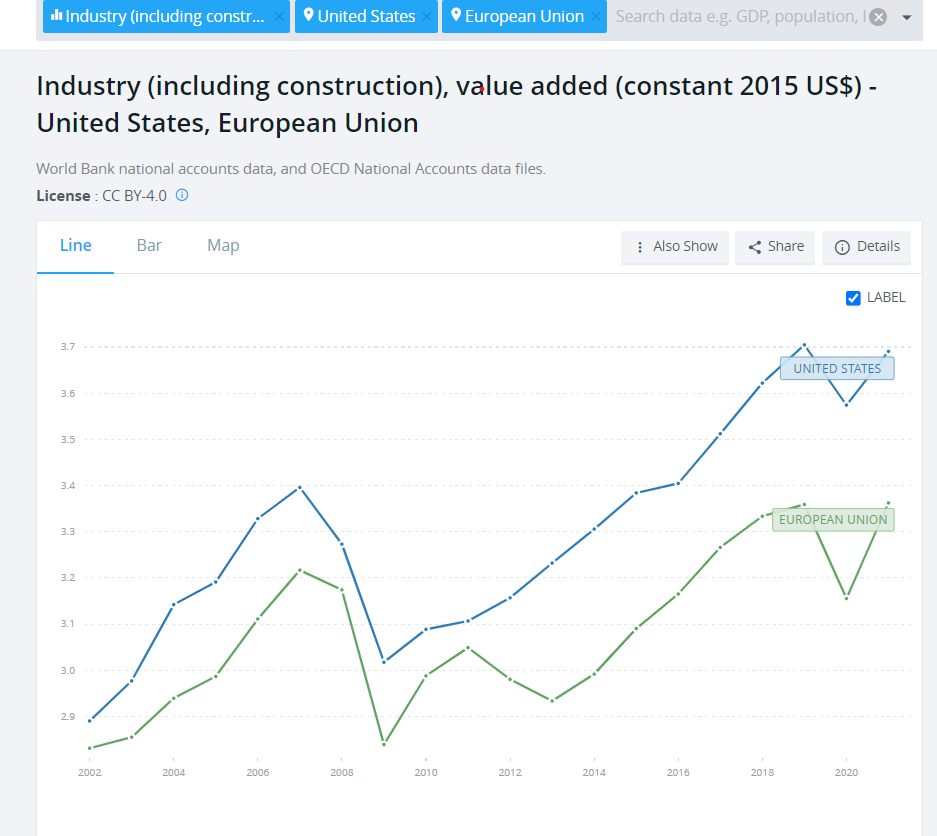

What the additional focus on manufacturing seems to be doing instead is accelerating a long-term trend of U.S. industrial power eclipsing that of Europe.

Figure 1: U.S. and EU industry (including construction) value added. Source: World Bank.

Figure: U.S. and EU manufacturing value added. Source: World Bank.

This trend was already underway in 2008 and was accelerated greatly by the fracking boom. The massive expansion of U.S. gas dropped oil and gas prices greatly. The result was that the U.S. electricity prices deviated greatly from those of Europe, leading to asymmetries in growth.

The U.S. has an abundance of fossil fuels, plenty of deserts for solar farms, and a nuclear sector that enjoys very high capacity factors (even with the troubles of construction). By contrast, Europe is stuck with high green levies, a sudden lack of Russian gas filled with expensive LNG imports, a creaking nuclear sector in France, and a relative lack of sunlight for new solar deployments.

Washington-led restrictions on Chinese technology acquisitions could hamper Europe’s industrial capacity further. ASML is Europe’s most valuable technology company and is critical to supplying semiconductor fabricators with the necessary machines to make advanced chips.

ASML is effectively banned from selling its most advanced ultraviolet lithography equipment to China. The U.S. government is hoping it can convince European actors to restrict technology exports to China through friend-shoring initiatives. But taking China out of the potential export market, no matter how you size it, is reducing potential export growth for Europeans.

The compact of the post-war period, often characterized as the liberal democratic order, rested on the U.S. allowing Germany and Japan to retain and rebuild their industries through access to the U.S. market.

In return, these countries would forego geopolitical competition and accept being under the U.S. security umbrella. Similar compacts were made with resource-rich countries like Saudi Arabia. Countries like Britain and France, who were not occupied and had their own pretensions towards world power status, were ironically less well-placed in this American-led system.

This order had one obvious casualty. The U.S. manufacturing base would have to compete with exports from jurisdictions with lower labor costs. Rather than remedy this when Japan and Germany recovered, the system was put into overdrive in 2000 with the opening up of trade to China. Global growth since 1945, to a large extent, has been determined by access to the U.S. consumer market.

This arrangement has become untenable, simply because export-led growth has turned China from an economic backwater into a scientific-industrial powerhouse that can seriously challenge U.S. geopolitical dominance. This is what is driving U.S. subsidies into its industry.

But while aimed against China, U.S. industrial policy could more likely weaken its allies, particularly but not limited to Europe.

As an example, the U.S. has become increasingly worried about the Russian and Chinese export of nuclear reactors. It has stepped up efforts to help its primary reactor supplier Westinghouse sell reactors to Eastern Europe. This has included funding from the export-import bank and state agencies to Romania to help build nuclear plants with U.S. suppliers.

South Korea’s Kepco, another nuclear supplier, has built plants for under a third of the cost the U.S. has managed and is also courting potential clients in Eastern Europe. They are as a result being sued on technicalities by Westinghouse with the backing of the U.S. government. In trying to reassert its own technical leadership, American authorities are hampering allies, not opponents.

The U.S. is in a difficult position. As it prepares for a multi-decade face-off against a capable opponent, it risks exacerbating stagnation amongst its allies. While the economic woes of Europe have more to do with bad domestic decisions than the White House, Gaullist criticism of undue American influence over European affairs could well become mainstream by the end of the decade.

"simply because export-led growth has turned China from an economic backwater into a scientific-industrial powerhouse that can seriously challenge U.S. geopolitical dominance. This is what is driving U.S. subsidies into its industry”??

Hmm. For a few years after China's WTO accession the goods exports saw 60% CAGR, but from a small base. But as a proportion of China's GDP, exports never led growth.

Today, Chinese exports account for 20% of GDP, vs. 32% for Canada and 47% for Germany, and 97 of of 'Chinese' exports to the USA are US-designed products manufactured by US-employed Chinese in US-owned factories.

Who would lose if that deal blew up? No more GM Certified Truck Parts...