Britain needs to drastically accelerate its nuclear plans

24 GW by 2050, with only 3 GW under construction and 6 GW coming offline by 2035. The government needs to execute a nuclear buildout in the next year.

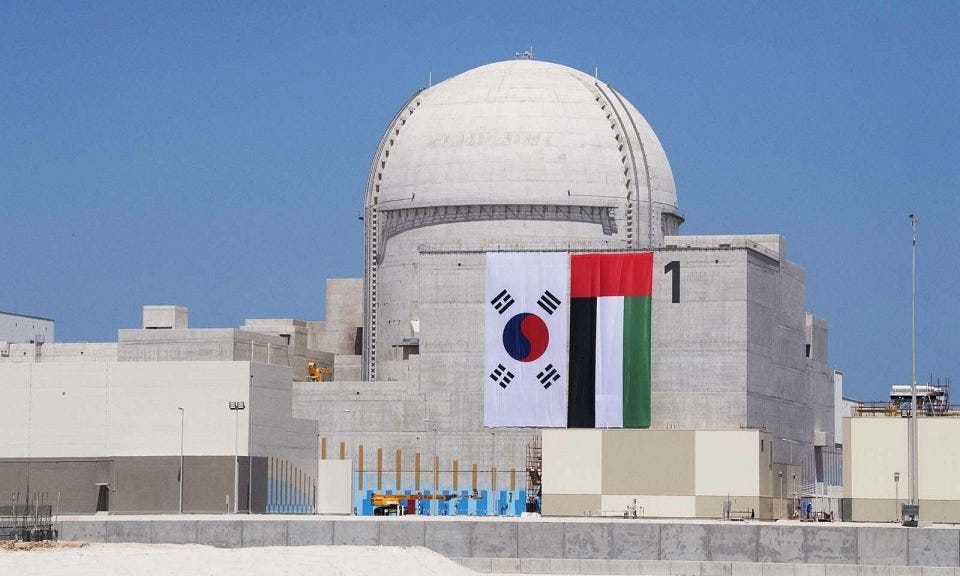

Could have been us….

The British government has a target for 24 gigawatts (GW) of nuclear capacity by 2050. Every gas-cooled reactor currently online is closing by 2030. Sizewell B’s light water reactor will be closed by 2035. The plant currently under construction at Hinkley Point C adds 3.2 GW. We therefore have to build a new fleet with a capacity of 21 GW from scratch. Given that Britain’s highest nuclear capacity ever was 13 GW, this is a daunting task.

The government's 24 GW is not matched by the projections of the National Grid. In the Grid’s future energy scenarios, the maximum potential for nuclear capacity by 2050 is 16 GW. For its “leading the way” scenario, nuclear capacity flattens at 10 GW. There is a clear gap between the government’s nuclear ambitions and the plans of the country’s largest utility.

For big plants to be built in a timely fashion, Britain needs a partner besides the French government. Sizewell C has been approved. But it still requires £20 billion in private financing. Other prospects for partnerships with the French nuclear industry are dubious, given the examples of significant overspending at both Hinkley in the UK and Flamanville in France.

South Korea’s Kepco is the most obvious partner for the development of large traditional reactors. It can build its functional light water reactors (the standardized APR 1400) for around $2500 per kw in Korea and around $4500 per kw in the UAE. It should theoretically be able to deliver plants in Britain for atleast a third of the price of Hinkley.

Figure 1: Prices of different nuclear construction projects in 2023 U.S. dollars from 1987 to 2023. Orange bars denote plants that have yet to establish a grid connection. Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

There is a snag. The APR 1400 has not started the generic design assessment (GDA) process with the Office of Nuclear Regulation (ONR).

The ONR currently has four reactor designs approved for construction: Westinghouse’s AP 1000, GE-Hitachi’s Advanced Boiling Water Reactor (ABWR), EDF’s European Pressurized Reactor (EPR), and China General Nuclear Power Group’s Hualong One.

All these four designs had to go through three steps; a preparatory step, a fundamental assessment, and a detailed assessment. This is supposed to take 48 months. The ABWR took the shortest time to approve at just under five years, between January 2013 and December 2017. The AP 1000 took nearly ten years, from April 2007 to March 2017.

Getting a GDA is just one step to building a nuclear plant. A nuclear site license must also be obtained from the ONR. Then the environmental permits must be obtained from the Environment Agency or Natural Resources Wales.

Finally, planning permission must be obtained from the planning inspectorate and BEIS. Much of this is subject to judicial challenge, and getting such approvals has no predictable timeline. Hinkley C was approved quickly, but Sizewell C (the same reactor configuration) took ten years to get approval.

Kepco’s APR 1400 has already been approved by the relevant U.S. and EU bodies, making a GDA in the UK an exercise in repetition. For South Korea to be a partner in nuclear, the GDA for the APR 1400 will surely have to be accelerated.

This would probably have to coincide with workarounds regarding the broader planning landscape for Britain. One proposal being considered is creating regulatory exceptions via ‘go-to’ zones where environmental permits are not required for key infrastructure. This feels like a tacit acceptance of our ridiculous planning system, but it is potentially expedient.

Then there are the small modular reactors (SMRs) being developed by Rolls-Royce. They are scaled-down light water reactors with 470 megawatts (MW) in capacity. They have already received some UK funding and are in the second stage of the GDA. The company has also established viable development sites through completing a site assessment with the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA).

It is then strange that Rolls-Royce has to enter a competition with other SMR developers to receive major investments from the British government. A final investment decision is not planned until 2029.

For context, GE-Hitachi is already approved to build its BWRX-300 reactor at Darlington in Ontario. The Korean conglomerate Doosan is forging components for the American SMR supplier Nuscale. China has built an SMR demonstrator and is completing a 100 MW light water reactor (the ACP100). Russia’s Rosatom has constructed a floating small nuclear power station and is hoping to export it. SMRs are nascent, but they are already here. By 2029, we will be well behind the curve on deployment.

It makes sense for the government to enter into a preferential relationship with a domestic manufacturer it has a golden share in. It already partners with Rolls-Royce for its naval nuclear propulsion systems. A smaller SMR competition could be retained for international developers but this would be supplementary.

Rolls-Royce claims to be able to build the systems at around $6,000 per KW, or around £4,000 per KW. If it can achieve this, this would be a marked improvement on Hinkley C ($12,500 per KW). This seems unrealistic for the first systems, but the lower capital cost of SMRs makes betting on the technology less risky.

Speed up the GDA for Rolls-Royce, support the domestic champion you are likely going to give the competition to anyway, and get moving in earnest now rather than in 2029.

Looking forward, this is a roadmap to get the nuclear capacity Britain needs by 2050. It assumes a partnership with South Korea and the deployment of SMRs at sites targeted by Rolls-Royce. Being pro-nuclear I would see this as a start, but it provides enough leeway to drop some projects. The success of the Rolls-Royce SMR is far from certain, so there may be a need for a third large Kepco reactor.

Figure 2: A proposal for new British nuclear capacity before 2050.

The government inherited a challenging target and has kept it. But it has not put a plan in place to action it. Given the challenges of variable renewables, a consensus is forming in Canada, France, China, the Netherlands, Sweden, India, Russia, Poland, Bulgaria, Czechia, Japan, Korea, and Britain that nuclear fission is worth the investment.

For Rishi Sunak, it might be the only real chance for a lasting legacy – the Tech-savvy maverick who, despite the objections of others, backed Rolls-Royce and turned Britain into a civil nuclear exporter. For Starmer, it would be a no-brainer to keep the target. He would be carrying out the great mission laid out by Blair in 2006. It is time to make a firm commitment and press ahead rather than wait for 2029.