Automation will be harder than the energy transition

Everywhere, countries are automating in a desperate attempt to increase productivity. Britain is barely in the game.

Until recently, there was a consensus that automation would create a tidal wave of superfluous people resulting from job losses. Famous thinkers like Yuval Noah Harari predicted a ‘useless class.’

This flew in the face of economic studies. A 2022 meta-analysis of 32 studies saw no clear link between robot use and employment. Papers found companies that automated were more likely to expand employment. Microeconomic studies for highly automated labor markets like Germany found a positive correlation between automation and jobs, even for low-skilled workers.

There are more simple indicators suggesting automation is not the scourge of employees. The largest client for industrial robots is the global automotive industry. From 2009 to 2017, employment in the auto sector grew from 10 million to 14 million, rising 19% in the U.S.,13% in Germany, 35% in Japan, 25% in Korea and 68%% in China.

Despite the hand-wringing about AI, deploying automation to increase productivity is difficult. The question is shifting from…

“How do we help the poor, useless people made redundant by AI?”

to…

“How much do we have to invest in automation to maintain economic growth while facing demographic stagnation?”

The energy transition will be difficult but achievable if the primary goal is decarbonization (maintaining growth will be very hard). The prospects for increasing productivity to sustain economic development are much less certain.

Britain’s place in robotics

It is now well established that the UK is one of the least automated nations in the developed world, below the world average. While the global average robot density was 141 per 10,000 manufacturing workers in 2021, for Britain it was 101.

While Britain is noted for being unautomated, the entire West is lagging behind its East Asian competitors. The three most automated countries are South Korea, Singapore, and Japan. In 2022, China’s manufacturing base, the largest in the world, was more automated than America's.

These figures are disputed, with some analysts arguing China’s manufacturing workforce is much larger than the IFR calculated. This implies that Chinese robotics has a lot of room still to grow.

Figure 1: IFR Robot density for 2021. Source.

About half of all robots sold are made in or go to China. While they are still heavily reliant on Japanese and European manufacturers for expensive industrial arms, they are beginning to export cheaper service robots to nearby markets like Korea. In 2022, 70% of the service robots sold in Korea were Chinese.

The Chinese government is affirmative in embracing robotics. The scale of its investments is staggering. In August 2023, the municipal government of Beijing alone set up a $1.4 billion fund to invest in robots. This is part of a broader plan for the city to spend $4 billion on automation by 2025.

British industrial policies are minor in size compared to those of Chinese cities. A larger national initiative, launched in early 2023, plans to double Chinese robot density from 2020 to 2025, making it more automated than Japan or Germany.

This is not guaranteed to pay off. Chinese productivity growth has slowed down considerably in recent years. All major economies are struggling to eke out productivity growth. Automation is critical to achieving this, but the more automated a production line becomes, the harder it is to squeeze productivity growth out of it.

The problem for Britain is that robotics are capital-intensive, require a lot of engineering expertise to deploy at scale, and are heavily weighted towards large manufacturers with access to deep capital markets.

Britain is relatively capable of manufacturing cheap service and consumer robots. An example is the Husqvarna factory in Durham, which has manufactured millions of robotic mowers. However, the country is lagging when it comes to mass adoption in the industrial and commercial sectors.

A significant reason for this is constrained capital expenditure. According to the Bank of England, net lending to manufacturers has never recovered from the 2008 crash.

Figure 2: 1993 - 2022 Annual amounts outstanding of UK resident monetary financial institutions sterling and all foreign currency net lending to manufacturers (in sterling millions) not seasonally adjusted, Source.

Robots are capital-intensive, risky, and often unprofitable

Trepidation is also a factor. Robots, despite their promise, are far from guaranteed success. Some of the SPACs of the post-Covid recovery have already failed. Berkshire Grey, a warehouse automation company, was threatened with being delisted and had to merge with Softbank.

The U.S. equipment manufacturer Teradyne has, since 2015, bought four major robotics companies, which now make up 13% of its revenue. But it is losing money on them, while its profits are made in established markets like testing semiconductors.

Figure 3: Teradyne 2022 sectoral revenue. Source.

Figure 4: Teradyne 2022 Income Profit/loss by segment. Source.

In 2020, Walmart, the world’s largest company by revenue, dropped the scanning robot company Bossa Nova from its stores. Regarding groceries, the most notable new company is Instacart, which provides delivery from personal shoppers at low wages. Gig workers are currently far more valuable to retail and transportation than robots.

Sarcos, a developer of more futuristic technologies, including exoskeletons and giant teleoperated robotic arms, made $1.3 million in the second quarter of 2023, with a net loss of $28 million. The technology is impressive but beyond the financial means and expertise of most potential customers.

Ocado is one of the bright spots of British automation and recently won a legal battle with Norwegian automation firm Autostore. The company has been buying robotics firms for some time. It acquired U.S. robot maker 6 River Systems from Shopify for $12.5 million. Shopify lost a considerable amount from 6 River, initially paying $450 million for the company in 2019.

This is one of many examples of robot startups being bought at cheap prices. Ocado itself has been criticized for not turning in healthy returns.

Despite the poor finances of many robotics companies, the systems themselves are proliferating. Amazon went from having no mobile robots in 2012 to 750,000 in 2023, the largest fleet in the world. The enormous capital required to fund these fleets is heavily subsidized by Amazon Web Services, the corporation's highly profitable cloud platform. While Amazon’s human workforce contracted from a massive high in 2022, its mechanical and biological workforces have grown in sync.

Figure 5: Number of robots and employees at Amazon. Sources are various and based on official press releases.

Robots are mostly the preserve of big companies who are comfortable with very high CAPEX. This is where the British disadvantage is most apparent.

Automation - the real challenge for our times

The enormous Chinese investments in robotics are likely no more than a precursor to the trillions worth of investment over the next few decades. In search of elixirs to productivity slowdowns, corporations and countries will have to spend amounts comparable to the much more discussed energy transition. But while venture capital investments in robotics totaled $90 billion between 2018 and 2023, renewable energy investments totaled $1.3 trillion in 2022 alone. This gap will have to narrow.

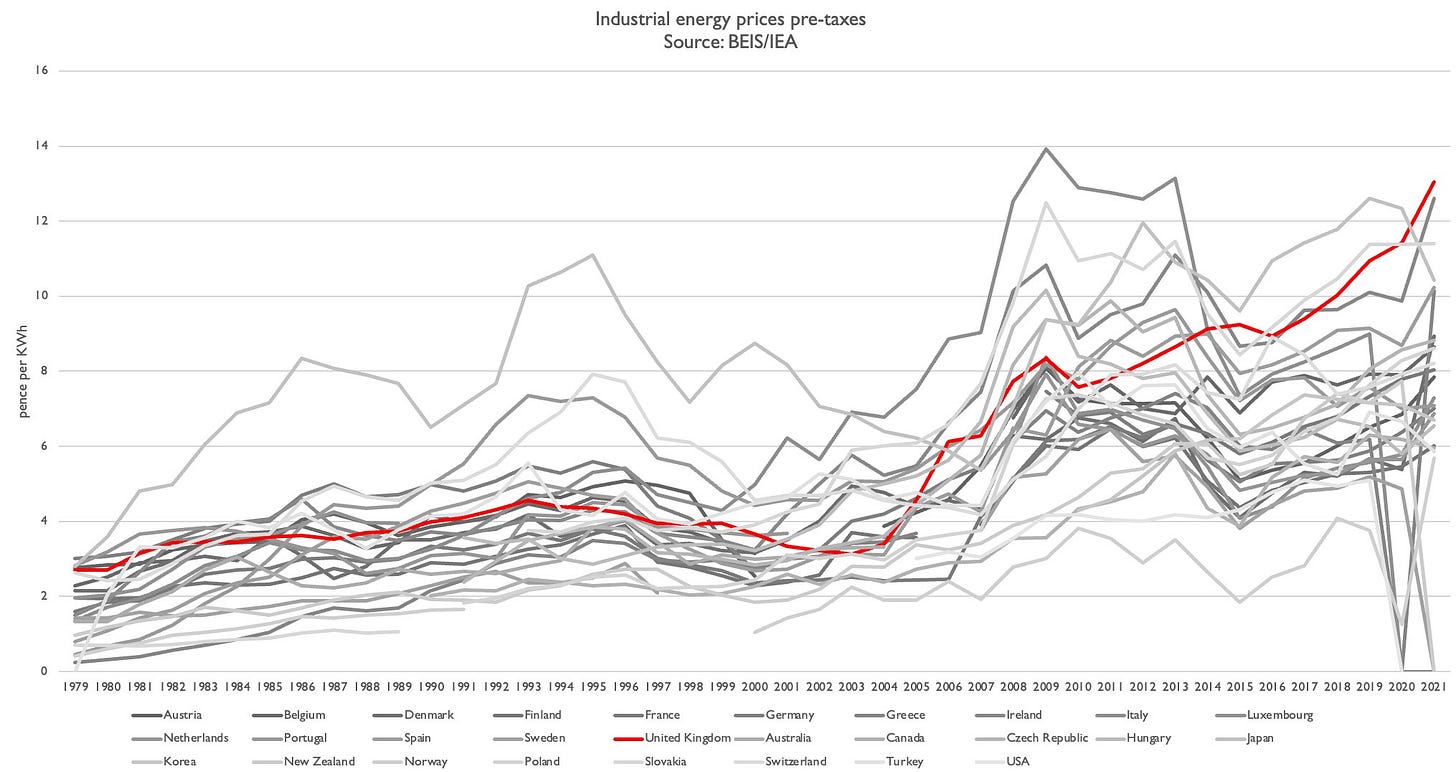

Where does this leave the automation-laggard Britain? We have the highest industrial electricity prices in the rich world and an anemic investment scene for manufacturers. This is a poor platform from which to undertake an automation drive.

Figure 6: Industrial electricity prices. SouU.K.e: UK Government via Ed Conway

The lack of government interest in automation starkly contrasts our fretting about Net Zero. Britain has been remarkably good at scaling back its carbon emissions and energy usage. It has deployed intermittent renewables at scale. All of this has almost no effect on global emissions. Its benefits to the economy are dubious at best and ruinous at worst.

By contrast, we spend little time thinking about automation, where we are deficient. We will become even more of a spectator unless we alter our priorities.

Chinese productivity growth has slowed down considerably in recent years??

Our media get away with claims like this but they’re eliding ‘growth’ and ‘rate of increase’ (usually %). In reality, China's economy is red hot.

China's GDP is $30 trillion PPP

5% growth = $1.5 trillion.

$1.5 trillion = more than the GDP of 192 countries.

$1.5 trillion = more than US + EU growth combined.

$1.5 trillion = 30% of global growth*.